|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“Words cannot describe the Excellences of Martin,” writes Sulpicius Severus, hagiographer of the fourth-century St. Martin of Tours. “Never was there any word on his lips but Christ, and never was there a feeling in his heart except piety, peace, and tender mercy.” Yet some, such as academics and activists, now look askance at this Roman soldier-turned-saint.

I encountered this several years ago when emailing with an old friend who is now an accomplished professor of Classics at a top-tier university. My friend argued that Severus’ The Life of St. Martin of Tours “is actually quite disturbing.” He continued: “Martin does a lot of stuff that—even in the glowing and embellished presentation of a work of hagiography—pretty unambiguously amounts to attempts to extirpate local culture tout court.” In other words, according to the twenty-first century multiculturalist, Martin of Tours is a cultural imperialist.

What, exactly, is my friend talking about? Before we get into that, it would be useful to offer a very brief biography of this saint. Martin was a native of Pannonia, in what is now part of Hungary, Slovakia, and Austria. Because his father was a retired senior officer in the Roman military, he grew up in northern Italy. Against the advice of his parents, Martin became a catechumen in the Church, though he entered military service as a teenager.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

After being released from military service, Martin became a disciple of Hilary of Poitiers, who would, in time, become a doctor of the Church. Martin embraced an ascetic life, and after various travels, he became bishop of Tours in A.D. 371. He was a faithful, prominent leader of the Church in France until his death in 397.

So, what about Martin of Tours leads contemporary academics to label him a cultural imperialist? Several stories from his hagiography, most having to do with local religious customs, explain.

Severus describes a certain village who had “demolished a very ancient temple,” and were preparing to cut down a sacred pine tree, provoking the ire of a local priest and his pagan followers. “These people,” writes Severus, “though, under the influence of the Lord, they had been quiet while the temple was being overthrown, could not patiently allow the tree to be cut down.” Martin, however, told them the tree possessed no sacred power and that the tree needed to be cut down because it had been dedicated to a demon. The people agreed to cut it down if he would “receive it,” (i.e., stand in its way) as it fell. After the tree did not (miraculously) hit Martin, many locals converted to the Catholic faith.

By this author:

-

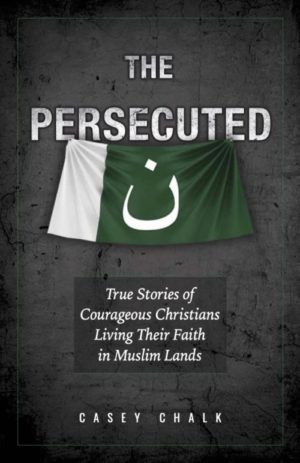

The Persecuted$9.95 – $18.95

In the very next chapter, Severus describes a village named Leprosum, in which there was a “temple which had acquired great wealth through the superstitious ideas entertained of its sanctity.” Severus writes that “a multitude of the heathen resisted him to such a degree that he was driven back not without bodily injury.” Yet Martin withdrew, praying and fasting “in sackcloth and ashes,” beseeching the Lord that the temple might be overthrown not by human effort but by “divine power.” With the help of angels, Martin returned to the village, razed the pagan temple to the foundations, and “reduced all the altars and images to dust.”

Finally, Severus relates “what took place in the village of the Ædui,” where Martin was “overthrowing a temple.” In response, “a multitude of rustic heathen” attacked Martin, who “offered his bare neck to the assassin.” Though the enraged man raised his arm to strike Martin, he was “overwhelmed by the fear of God” and begged for forgiveness.

Demolishing idols and temples is what multiculturalist academics and activists take issue with when it comes to Martin—and not only the ancient saint, but more recent Catholic missionary activities in the Americas, Africa, and Asia (see recent controversies in Canada). And, in one particular sense, they’re right: historically, Catholics have quite zealously sought to repudiate and even disrupt local cultural practices they perceived as unequivocally morally reprehensible.

As a lover of history and frequenter of museums, I can appreciate a distaste for Catholic destruction of what we could consider priceless archaeological objects that shed light on various ancient peoples and their cultural practices. And I’d imagine few Catholics, and certainly not the Catholic hierarchy, would encourage going around tearing down statues of Greek and Roman gods and goddesses in Italy or Greece, or inside various museums. (Albeit few if any people today worship the Roman or Greek pantheon, so they’re not exactly a contemporary threat.)

Nevertheless, however much we might learn from such artifacts, we should not be too quick to judge the acts of those who judged them so existentially dangerous at a particular moment in history that they required obliteration. Our knowledge of Aztec human sacrificial practices, for example, is sorely limited by the fact that the Spanish conquistadors and missionaries so thoroughly dismantled it. Was there something intrinsically evil in the materials used in Aztec art? Hardly.

But those materials had become so intimately wrapped up in a brutally wicked religious system—sacrificing tens of thousands of people every year—that their destruction was required to (wait for it) extirpate a particular practice from Aztec culture. It wasn’t that all of Aztec culture was bad—indeed, the tilma of Tepeyac proves Catholic approbation of certain elements of that culture. But sacrificing people to demons cannot be countenanced. We can cite many similar examples: from the violent blood-feuds and misogyny of various indigenous peoples of the Americas to the genital mutilation of various African tribes, Catholic missionaries have been willing to combat and defeat cultural practices they deem to be antithetical to human flourishing.

Granted, I’m no expert on fourth-century religious and cultural practices in Roman Gaul. As far as I know, there was no human sacrifice among these peoples. We know temple prostitution was common in various parts of the Roman world, so perhaps such things happened in Martin’s “missionary territory,” but perhaps not. We do know Martin had traveled a good bit throughout the Roman Empire, so undoubtedly the pagan practices of Gaul, whatever their local flavor, were likely not unfamiliar to the former soldier. Yet something about pagan idols and temples so concerned Martin that he assessed them to be a threat to worship of God and formation of a Christian society in what would in time become the “eldest daughter of the Church.”

It’s possible Martin’s actions against Gaulish-Roman paganism were unnecessarily aggressive, though if his hagiography is to be believed, the Gauls accepted, and even embraced, his Christianization efforts with little physical coercion. If anything, they were the ones able to do the coercing, as Severus’ stories indicate. Perhaps they, albeit not without resistance, came to realize the vain worthlessness of their pagan worship. If Christian “cultural imperialism” is what it took to cultivate a nation that gave us the temples of Chartres Cathedral and Notre Dame, as well as St. Louis, St. Louis de Montfort, St. Francis de Sales, St. Isaac Jogues, St. Bernadette, and St. Therese of Lisieux, the loss of some temples and idols seems a trade worth making.