Fr. George Rutler needs little by way of introduction to Crisis readers. He has been gracing its pages, first in print and then online, for just shy of four decades.

Recently, Crisis caught up with Fr. Rutler for an interview on his life as a priest-writer to mark the publication of his latest collection of writings.

¤ ¤ ¤ ¤

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

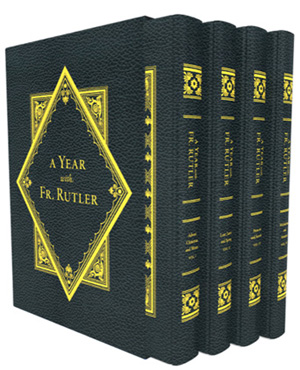

You have published many articles; some have been collected into books. The latest collection from Sophia Institute Press comprising a box set of four leather-bound volumes seems to be on a different scale entirely. How did this latest collection come about?

RUTLER: Others suggested the publication of a four-volume set that followed the liturgical year. I agreed to it rather hesitatingly, since the columns were not originally intended for a readership wider than a local parish. One is not invariably the best judge of what will be most useful as a permanent record. I recall a line of the Anglo-Irish novelist, Shane Leslie, who, when pressed to write an introduction to the ponderous autobiography of a prelate, managed to say that a chief charm of the author was his innocent assumption that what interested him would also be of interest to readers. The prelate was sufficiently full of himself to take that as a compliment. So I let others rummage through the files and take their pick. The real work was that of the general editor who gracefully made what must have been a heavy labor seem effortless.

How does it feel to see so many of your articles collected into one place?

RUTLER: My first reaction was one of surprise, that there was so much material. I hope it is not a testimony to a wasted life, but at least it is assuring to know that there were circumstances in the ordinary course of events that have application as time moves on. It is not unlike looking through a scrapbook, not in a nostalgic way but more like building a foundation for dealing with challenges yet to come.

When you look through the collection’s contents do you see any recurring themes in your writing?

RUTLER: One theme is the obvious, but neglected, fact that there are truths that perdure through the distractions and conceits of a superficial culture. Another theme is one I explored in a little book I wrote, Coincidentally, and which is easily sustained by experience: nothing that happens should be passed off as mere happenstance. In the light of grace, God is working his purpose out through daily events. A parish is a microcosm of society; this is evident in the crises experienced by parishioners, and perhaps even more dramatically in the daily routine of living which is boring only to the spiritually myopic. These are themes familiar to every parish priest, which is why there is no vocation more fortunate than his, and that sacred calling is made more luminous by the frustrations and trials that burnish it.

What has been the reaction to this latest collection?

RUTLER: This has been published only recently, so I have not received many comments, but I am gratified that over the years there have been notes and questions from far-flung readers. One does not think of that audience, because it would make one too cautious. What has surprised me is the frequency with which people express surprise that I have pointed out things that seem to me obvious. I hope that the beautiful bindings of these gilded volumes will not make the reader disappointed with any less artful contents.

What do you think makes for a good essay?

RUTLER: Most of what is included in these volumes was not written as essays, but rather as pastoral letters. But any article, essay, or letter should simply have a point to make and should, in addition to making it, explain why it is made. In writing of any sort, it helps simply to enjoy language. I cannot complain about the “social media” because the communications revolution, one of the most important developments in human history, has made it so easy to reach people. I think Saint Paul would have loved this, and would have used it to leave us many more epistles. But a danger in fast and abbreviated communication is the possibility of losing an appreciation of the beauty of language and the logic that it expresses.

And what advice would you give any aspiring writer?

And what advice would you give any aspiring writer?

RUTLER: Write regularly according to a disciplined schedule, like physical exercise. Do not write for the ages, but for people, and do not try to be lapidary. If you persuade or edify one soul, you have done your job. And enjoy the discipline of imposed word limits. They can be an affront and even an agony if you think that everything you have written is worth the writing. Deleting bits in order to cut the essay down to size can actually be invigorating, like a sculptor chipping away and then polishing what is left. Often, what an author thinks are the cleverest lines should be the first to go. Avoid jargon, which indicates an unclear mind, and abstain from exclamation marks, for they are a kind of semantic burlesque, calling attention to one’s inability to get attention without the use of a verbal neon light. Never weaken your prose with the flaccidity of split infinitives. And instead of being corrupted by popular magazines, syndicated columnists, celebrity writers, and pedantic translations of the Scriptures such as the New American Bible, spend time reading the great classics aloud. The contents do not matter: just get used to the sound. For verbal architecture, resist writing Corinthian until you have mastered Doric. Even the language itself is secondary to the rhythm. Once on a street corner in Manhattan I told a “hip-hop” performer that he was using the same dactylic pentameters of the “Odyssey.” I do not think that he absorbed the full portent of what I meant, but in that moment nearly three thousand years joined in song. While I may not have been a typical child in all things, any child is unjustly robbed if he is not allowed to experience the thrill I knew as a youth hearing the classical use of iambic pentameters to replicate the sound of horses’ hooves.

Often online under your writing there is the “comments” section. Do you read the comments? If so, what do you make of these immediate reactions from your readers?

RUTLER: Sometimes the comments are more interesting than that on which they are commenting. Many of the commentators go off on tangents, but I have not always been innocent of that myself. On my way into Purgatory, if I make it that far, I shall have to explain why I delectated on nice comments, and wished that less flattering commentators would soak their heads (but not fatally.)

Your primary vocation is as a priest. Do you see your vocation as a writer as something secondary or complementary, or is it something completely different?

RUTLER: The gigantic priests, starting with the holy Evangelists, saw writing (or dictating to their amanuenses) as an essence of their vocation, and never insulted the Good News by treating writing about it as an avocation. Evangelists are not dilettantes. As the Fathers always taught, the chief office, primum officium, of the priest, is to proclaim the Word, and this involves words spoken and written. Only Christ himself did not write, and that was because he is the Word.

Who are your literary heroes?

RUTLER: What a question! Everyone who struggles to write must look upon all other writers as some sort of heroes, even the heroic failures. One learns as much from the mistakes of others as from their masterworks. Everyone knows the greats. To cite Shakespeare as a model writer is like calling Moses an accomplished jurist. But there have to be in any practical pantheon of scribes at least among the many: Milton, Swift, Austen, Gibbon, Burke, Newman, and, to update, Wodehouse and Muggeridge. One prays that in these tempestuous times, there might appear such erudition among our earnest spiritual fathers in the episcopate, for the field right now is pretty barren and bleak. There are some apologists among them who stand out, but that is only because, as Erasmus said, “in the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king.”

Is there something new you would like to try in the field of literature? A novel? A play? Poetry?

RUTLER: I have experimented with verse and published a couple of hymns, for which I also composed the music. I did have a couple of poetry teachers who encouraged me and from time to time I think up mental odes in their honor: Richard Eberhart and Robert Frost. On the back burner is an accessible biography of Saint Louis IX. If I live long enough to attempt an Apologia, it would be in the form of a memoir of my life here in the Church in New York.

Why do you continue to write?

RUTLER: I expect to publish my thirtieth book in 2019. I am surprised that almost all of them still are in print. One of my earliest was on the epistemology of Immanuel Kant, but I have been unsuccessful so far in getting it made into a Hollywood musical. It is not that I have nothing better to do. My parishioners have an unmitigated tendency to get born, marry, and die, and this occupies one’s attention. Most of my writing is in pastoral response to events of the day, and I have to write between Holy Hours and plastering walls and fixing an antiquated heating system. But I continue to write for the same reason that I continue to breathe: I shall only stop when the Holy Spirit rejects the manuscript which is my life itself, and which is in dire need of editing.