Seventy-five years ago, Hans and Sophie Scholl were guillotined, just four days after the janitor at the University of Munich caught them distributing anti-Nazi fliers. She was 21, he 24, but they went to their death courageously, peacefully. They had stood up against the lies of the Third Reich, its contempt for human life, especially for that of the Jews, its murderous wars, and the brainwashing of its citizens. The Scholl siblings are honored today for their courageous resistance. But attention is not drawn sufficiently to the source of their strength, namely their deep faith in God.

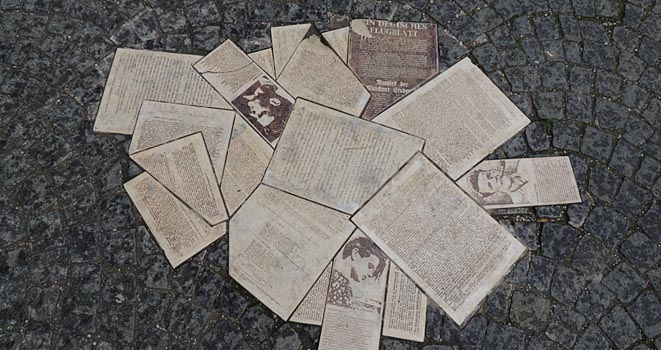

The Scholl siblings had joined the student resistance group “Die Weiße Rose” in Munich together with others in the spring (Sophie slightly later) of 1942. They were writing, printing and distributing fliers through other like-minded students in cities in southern Germany and eventually in Hamburg. Hans was studying medicine, Sophie philosophy and biology. Once caught, they took responsibility for everything, wanting to protect their friends—but they couldn’t prevent their close collaborators (Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf (who is being considered for beatification), Christoph Probst and Professor Kurt Huber) from being executed as well.

Though they came from a wonderful family—their father had always been critical of the Nazis, calling Hitler “the scourge of Germany” while their mother transmitted to them the faith (they were practicing Protestants)—they had felt the lure of the Zeitgeist, packaged attractively through the Hitlerjugend and the Bund Deutscher Mädel (the girl scouts). Yet they quickly lost their leadership positions once they started seeing through and speaking out against the Nazi ideology. They had already been arrested once in December 1937, for belonging to a forbidden youth group. Sophie was held one day, Hans for five weeks, but because of a general amnesty, no trial took place. This, if nothing else, opened their eyes to the totalitarianism of the Third Reich. They realized the horrors of war, were apprehensive about the fate of the Jews and of other people suddenly disappearing, and had the courage to act on their convictions. This eventually led to their arrest and deaths.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

As they left the courtroom, Hans had the time to cry out to the fanatical judge, Roland Freisler, who was famous for screaming at and berating defendants, that there was, still, a different justice than the one meted out to them. Freisler himself met that other, divine justice on February 3, 1945, when he was killed during a bombing, carrying the file of an accused who would otherwise have been condemned to death. Others had their day in court after the war.

The morning of her death, Sophie had her famous dream: she was carrying a baby clad in white up a hill towards a church where it was supposed to be baptized. While a crevasse suddenly opened up in front of her, she had the time to deposit the child on the other side before falling into it herself. She interpreted this to mean that their idea, their ideal of freedom (which was the last word she wrote on the back of her bill of indictment), would survive, that she had prepared its way even if she had to die in the process.

Those who have seen the movie The Last Days of Sophie Scholl will already have a good sense of what the Scholl siblings stood for and how courageously they witnessed to the truth during these last few days of their lives, though the film does not emphasize sufficiently their religiosity. Their sister, Inge Aichinger-Scholl questioned eye-witnesses and compiled interesting information gathered in 78 tightly written pages for her parents. She spoke to the pastor who had visited them in prison. He claimed one “could hear the rush of angels’ wings.” The executioner, Johann Reichhart, who carried out capital punishment on 3,000 people during the Third Reich, said he had never seen anybody die like that. Their parents, who rushed to the prison after their children had been sentenced, only had 10 minutes with them, but said Hans’ and Sophie’s faces were luminous.

Not only were they deeply nourished by their Christian faith, but one can also trace a significant Catholic influence in their life. The Catholic publicist Carl Muth and the thinker Theodor Haecker (convert and Newman translator) were among their close contacts; they were also profoundly influenced by Augustine, Pascal, the renouveau catholique, and scholasticism.

They understood that the crisis in Germany was not primarily a political, but a spiritual one. “Man is defenseless against evil without God,” they wrote in the fourth of their six fliers, for he is “like a ship without a rudder, abandoned to the storm.” They decried the apathy of people who are expecting somebody from the outside to free them from this “dictatorship of evil” as they called the Nazi state (third flier). But one cannot maintain one’s innocence while passively watching evil win: “for with every day that you still hesitate,” as they declared in their third flier, “that you do not resist this spawn of hell [i.e., Hitler], your guilt increases like a parabolic curve higher and higher.” They denounced the extermination of the Jews, calling it “the most horrific crime against the dignity of man, a crime, that is unlike any in the history of mankind” (second flier). In this context, one cannot doubt, they claimed, the existence of demonic powers, though this does not excuse human beings for giving in or failing to resist (third flier). At the very least, they suggested, passive resistance is open to everybody, sabotaging the regime wherever one can.

Like Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg who made a famous failed attempt on Hitler’s life with an insufficiently powerful suitcase bomb, the members of the “White Rose” hoped to succeed, but at the same time realized that in case of defeat, the significance of having tried was eminently important: for Germany then and for Germany later.

But what remains of their hopes for Europe, their desire for a spiritual revival (for “only religion can resuscitate Europe” and only Christianity could assure the peace, as they wrote in their fourth flier)? It is impossible to do justice to this question within a short article. But Germany—after having reawakened under the Catholic chancellor Adenauer to the importance of the natural law, the significance of Europe and determined that something like this should never happen again—has fallen prey to another deadly ideology just like the rest of the Western world. This ideology may not have—as yet—been imposed by a totalitarian regime in the West, even though democracies, as we have seen in Germany, can become totalitarian.

Christ accused the Pharisees of killing the prophets while honoring the tombs of the past martyrs, unaware that they are committing the same crimes as their ancestors. It is not enough to bow down in front of the graves of the Scholls and their friends, nor to imagine that new ideologies will look like past ones. This will blind us to the dangerous ones in our midst.

The current ideology seems to have achieved the squaring of the circle by combining what seemed merely a loose life-style into a Weltanschauung. It signaled its arrival with the Sexual Revolution, calling for a sexual liberation, the attractive glitziness of which was hiding the mounds of dead bodies and broken lives of women and families to come: more than two billion babies have been aborted worldwide since the cascading legalizations of abortion in the West starting over 50 years ago. Euthanasia, of which we are just seeing the beginning, is the logical consequence of this culture of death. And gender-ideology is the summit of utopian false thinking that human nature can be shaped into anything one wants it to be, trying to silence all those who think differently.

The Scholl siblings warned of apathy, more than of fear. Either way, the courage to withstand the Zeitgeist—which is not rigid stiffness (as Pope Benedict XVI said so well in a sermon to five newly ordained bishops)—and the willingness to act, is what we are called to now as the Scholls were then. Being centered in the truth requires being anchored in God. Prayer and action therefore need to go hand in hand: the latter must flow from the former. Only then will honoring courageous witnesses like the Scholls not remain mere lip-service.

Editor’s note: The lead image depicts Hans and Sophie Scholl with Christoph Probst (right) in Munich in 1942.