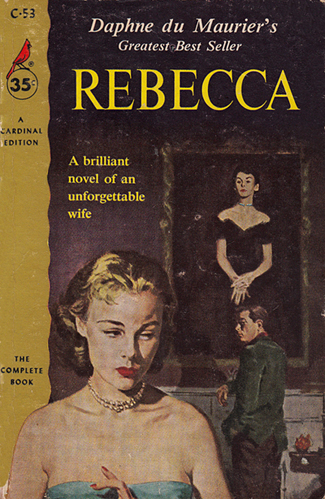

Every reader loves a good ghost story. And that is why Daphne du Maurier’s Romantic-Gothic novel, Rebecca has thrilled readers since its publication in 1938. The tale begins with a slight flavor of Jane Eyre: a wandering Byronic hero who meets a meek heroine, gauche and plain. Unlike Mr. Rochester, Maxim de Winter has no secret wife hidden in his attic. Rebecca de Winter is dead, drowned in a boating accident, and no legal hindrance lies between our lovers’ union. They marry after knowing each other for a mere two weeks, and he whisks her away to his sprawling mansion, Manderley. It is only after they have arrived that the new Mrs. de Winter begins to wonder whether she has acted too hastily and ventured into waters which run too deep, much like the former Mrs. De Winter…

Du Maurier is a master of suspense and foreboding, weaving an eerie web of mystery and psychological intrigue which catches the reader in its subtle yet strong threads. It is doubtless an entertaining read and a classic for those who enjoy macabre thrillers with unexpected twists. Those who may feel guilty spending valuable time reading novels that do not provide anything but entertainment, however, should not be fooled by its melodramatic exterior. Rebecca has plenty for the moral reader to consider.

Appearances Are Deceiving

While living, the late Rebecca appeared to everyone to be the perfect wife and mistress of Manderley. She was exquisitely beautiful, witty, charming, talented and universally admired. Our heroine feels ill at ease in her new role as mistress of a great house, especially when everywhere she turns, she finds the lasting touches that Rebecca left behind. Though no longer alive, Rebecca haunts the household still and our heroine feels the pressure to measure up to her predecessor. It’s no wonder that the new Mrs. de Winter feels insecure and intimidated. Maxim tells her that Rebecca’s “taste made Manderley the thing it is today … the beauty of Manderley that you see today, the Manderley that people talk about and photograph and paint, it’s all due to her, to Rebecca.”

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

We soon learn, however, that Rebecca is rife with that oh-so-common yet oh-so-poignant theme in literature: things are seldom what they seem. There are countless household examples that illustrate this idea from Aesop’s wolf in sheep’s clothing to Wilde’s Dorian Gray and George Wickham in Pride and Prejudice. “Fair is foul and foul is fair” croak the three witches at the beginning of Macbeth, exposing the shallowness of evil and its attempt to simulate goodness. For that is all evil can really do: present a cheap mockery, an empty shell of what is truly good and beautiful. Things may be very different than how they appear to the eye of the beholder. Notwithstanding its dark tone, deeply flawed characters and grim ending, Rebecca offers several insights into the human condition, and foremost of these is how easily one can be taken in by appearances.

We soon learn, however, that Rebecca is rife with that oh-so-common yet oh-so-poignant theme in literature: things are seldom what they seem. There are countless household examples that illustrate this idea from Aesop’s wolf in sheep’s clothing to Wilde’s Dorian Gray and George Wickham in Pride and Prejudice. “Fair is foul and foul is fair” croak the three witches at the beginning of Macbeth, exposing the shallowness of evil and its attempt to simulate goodness. For that is all evil can really do: present a cheap mockery, an empty shell of what is truly good and beautiful. Things may be very different than how they appear to the eye of the beholder. Notwithstanding its dark tone, deeply flawed characters and grim ending, Rebecca offers several insights into the human condition, and foremost of these is how easily one can be taken in by appearances.

Jealousy Is Deceiving

Du Maurier described her work as a “study in jealousy,” and its corrosive nature can be seen throughout the novel. The current Mrs. de Winter allows her insecurities and jealousy of Rebecca to take complete control. As the narrator, she gives us a direct view into her thought processes and emotions and the result is exhausting. She is forever reminded of Rebecca’s capability as she learns the ropes of being a mistress of a great household. Not only that, she continually senses Rebecca’s presence in the house, feeling her gaze through the skull-like features of the ancient housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers.

Rebecca, always Rebecca. Wherever I walked in Manderley, wherever I sat, even in my thoughts and in my dreams, I met Rebecca. I knew her figure now, the long slim legs, the small and narrow feet. Her shoulders, broader than mine, the capable clever hands. Hands that could steer a boat, could hold a horse. Hands that arranged flowers, made the models of ships, and wrote “Max from Rebecca” on the flyleaf of a book.

As a result, she is constantly imagining what everyone is thinking of her, from the community, the servants, Mrs. Danvers, to Maxim himself. Her paranoia becomes so strong, in fact, that she almost commits suicide while a hopeful Mrs. Danvers encourages her to end her mental pain. Rebecca illustrates the winding descent jealousy can lead the unsuspecting mind. Dante defined the sin of jealousy, or envy, as the “love of one’s own good perverted to a desire to deprive other men of theirs.” In his Purgatorio, the envious are punished by having their eyes sewn shut with iron wire, a graphic depiction of what their sin has done to them. They are blind to the goodness, truth and beauty around them. Instead of focusing on her own relationship with her husband, Mrs. de Winter torments herself with thoughts of Rebecca and convinces herself that Maxim is still in love with her, imagining smoke when there is no fire.

Femininity Is Deceiving

Although on the surface it would seem that of the two women central to this story, Rebecca is the greater of the two in every aspect, du Maurier delivers a subtle reminder of where true worth lies. Though Rebecca was charming, talented and radiantly beautiful, she did not compare with the present Mrs. de Winter in Maxim’s eyes. He is attracted not by his present wife’s outward manner, but by her inner beauty, her simplicity and modesty. Just as “All that glisters is not gold” is found in Rebecca, the opposite is found in our heroine: “All that is gold does not glitter.”

Tolkien’s re-working of Shakespeare’s famous proverb reminds us that goodness can often be cloaked in unassuming garb as well. Mrs. de Winter’s simple, humble nature is contrasted to Rebecca’s ostentatious elegance. Maxim’s sister declares she “is so very different from Rebecca” which, though at first portrayed negatively, becomes a compliment once we learn Rebecca’s true character. Real beauty does not lie in one’s features or figure, not even in worldly admiration or achievements but in pursuit of virtue. Rebecca’s exquisite beauty crumbles for it lacks love for her fellow man and, ultimately, God. “Favor is deceitful and beauty is vain: the woman that feareth the Lord, she shall be praised” (Prov. 31:30).

The Title Is Deceiving

The most brilliant aspect of Rebecca is at the same time the most underrated. We are given an innominate heroine (she is only ever known as Mrs. de Winter) and we never meet the titular character who nevertheless haunts the pages with more vivacity than the rest of the cast. Rebecca is described as “so full of life” and, indeed, the current Mrs. de Winter feels her presence throughout Manderely as though she were still alive:

She was in the house still, as Mrs. Danvers had said; she was in that room in the west wing, she was in the library, in the morning-room, in the gallery above the hall… Her footsteps sounded in the corridors, her scent lingered on the stairs. The servants obeyed her orders still, the food we ate was the food she liked. Her favorite flowers filled the rooms. Her clothes were in the wardrobes in her room, her brushes were on the table, her shoes beneath the chair, her nightdress on her bed. Rebecca was still mistress of Manderley. Rebecca was still Mrs. de Winter. I had no business here at all.

Rendering a dead character among the most intriguing of the book is no easy feat, but du Maurier does it with such skill that the reader hardly notices. Nor is this the only occurrence where the reader finds himself drawn in before realizing what has happened. Rebecca muddies the moral waters with deceptive appearances, and readers are left to grapple with the perplexing dilemma facing these fated lovers. Not all the choices made are admirable ones, but though some may be left wondering with whom to side by the end, Rebecca offers poignant reminders of man’s fallen nature and his need for redemption. For what else is redemption but a proper interpretation and response to the needs of fallen nature? Rebecca stands ready and watching on the shelf. Do you?