“The noble person concerns himself with the root; when the root is established, the Way is born.” ∼ Confucius, Analects 1.2

Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option has run the critical gauntlet for the past two years, earning praise, critique, and cautious assessment from both the Christian and secular press.

While there is much that is praiseworthy and much that is “cringe-worthy” about Rod Dreher and his ever-increasing body of often awkward but, at times, prescient prose, there is little doubt that The Benedict Option (TBO) is among the most important Christian books of the twenty-first century.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

In many ways, TBO is a sequel to Dreher’s 2007 manifesto of hipster conservativism, Crunchy Cons, a work very much out of place during the watershed moment of neoconservative and evangelical Christianity of the George W. Bush era.

However, during the odd era of Pope Francis “LeftCat” liberalism and Donald Trump populism in which formerly solidified post-Cold War and post-Vatican II political and religious identities have been overturned, The Benedict Option has found a home among many Christians who hope to reboot Christendom by re-grounding themselves in their local parishes and communities.

A deluge of books has followed in TBO’s wake, hoping to tailor Benedict Option to a Catholic fit.

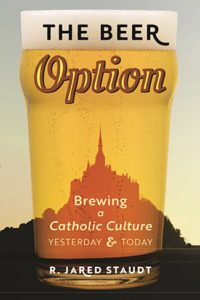

Among the most intellectually rich and sober works is Catholic author and catechist R. Jared Staudt’s The Beer Option: Brewing a Catholic Culture Yesterday & Today (New York: Angelico Press, 2018).

Combining Staudt’s expansive erudition of a professor along with the charm and wit of a “Catholic dad,” The Beer Option is a rare artefact in the post-millennium world of Catholic publishing, which is all too often defined by acrimonious debate. Happily, the book also avoids the pitfalls of many LeftCat hipster environmental works, for The Beer Option is firmly rooted in the spirit and teaching of Catholic orthodoxy.

Staudt’s central argument in The Beer Option is that the fermentation of Catholic culture so desperately required in our weary “Post-postmodern” age (yes, there is such a term) must have as its central ingredient a renewal of Catholic brewing and beer culture.

Staudt’s thesis is predicated upon a traditional and historical foundation of faith and reason.

Beer, we all know, is as old as human civilization itself. Recent research has shown that some sort of rice beer was drunk as early as 7000 BC in Jiahu, China, and there are traces of the more familiar Western barley beer drunk by the Persians dating back to 3500 BC. However, more important (and perhaps more interesting) is the fact that, as Staudt notes, beer has always been an impetus to culture. There is, for example, an 1800 BC hymn to the Sumerian goddess Ninkasi, praising her as “the one who soaks malt in a jar.” The hymn to Ninkasi is an early example of what will become one of the most treasured genres in the human song book: the drinking song.

Beer, we all know, is as old as human civilization itself. Recent research has shown that some sort of rice beer was drunk as early as 7000 BC in Jiahu, China, and there are traces of the more familiar Western barley beer drunk by the Persians dating back to 3500 BC. However, more important (and perhaps more interesting) is the fact that, as Staudt notes, beer has always been an impetus to culture. There is, for example, an 1800 BC hymn to the Sumerian goddess Ninkasi, praising her as “the one who soaks malt in a jar.” The hymn to Ninkasi is an early example of what will become one of the most treasured genres in the human song book: the drinking song.

Thus the creation and consumption of alcohol has always been a catalyst to human culture.

However, while the pagan cultures were notorious in their excessive and ecstatic consumption of beer (and wine among Mediterranean people) embodied by the wild (and often violent) god of eating, drinking, and merrymaking, Bacchus, Staudt notes that, via the Benedictine monastic movement, beer drinking, like the Northern European barbarians who drank it, was tamed and, in a certain sense, sanctified.

Although in his Rule the Italian St. Benedict of Nursia famously proscribed “a hemina [half a pint] of wine a day” for those monks who could not abstain from drinking, as the need for brew (and the vastly more important need for grace) grew among the wreckage of the collapsing Roman Empire, the Benedictines took up the task of filling mugs and saving souls.

The Benedictine monks, in fact, created beer as we know it, adding boiling of the soaked barely before fermentation, thus making beer more sanitary, and adding hops as a flavoring to the previously fermented medley of fruit, honey, and herbs—strange flavors that would make a comeback in the twenty-first century.

Benedictine learning filled labyrinthine libraries with the treasures of Greece and Rome and, in effect, rescued Western Christian civilization. So, too, would Benedictine beer mold not simply the Western palate but also shape the urban landscape of Europe and, later, the world.

Munich, Germany, famous for its weissbier and Octoberfest, derives its name from the German word for monk, “Mönch,” and two of the oldest and most famous breweries in the world, dating back to the eleventh century, Weihenstephaner and Weltenburger, began as Benedictine projects.

However, as Catholic culture began to erode in the Modern era, so, too, did the Catholic sacralization of beer brewing and drinking fracture.

As is commonly known, the attack on Catholicism, beginning with Protestant prudishness and escalating into violent and ignorant Enlightenment bigotry, focused on monasteries as centers of papist decadence, laziness, and superstition.

Sixteenth-century reformer, John Calvin, in his Harmony of Law, castigated monks for their abstinence from food, but “license in drinking” and the intellectual movement that Calvin spawned snowballed into an “unintended reformation.” This created a dichotomy between the profane and sacred, and thus, as Staudt brilliantly notes, alcohol became a strange and demonic force in many Protestant cultures.

No longer was the monastery and the monastic brewery the center of Christian culture. As the West industrialized, so, too, did the production of beer, creating the doubly strange phenomena of the industrial work week as well as, in the twentieth century, the industrially produced Coors Light.

Thus was born, in Staudt’s reading, the soulless and at best, nominally Protestant “hellscape” of our atomized industrial and, now, post-industrial Western society, in which our existential sorrows are drowned with a case of Michelob.

Staudt’s solution—his “Beer Option”—is a return to small brewing as part of a wider and more expansive Benedict Option of creating intentional Christian communities focused upon seeding a localized Christian culture.

Drawing from the Distributism of G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc as well as the Catholic Land Movement of Fr. Vincent McNabb, Staudt argues for a revival of microbreweries and the eccentric but delightful phenomenon of home brewing. The objective would be to tame what Catholic writer John Horvat has called the “frenetic intemperance” of the modern world as well as the oppressive and suffocating “Post-postmodern” phenomenon of global capitalism, which, as Dreher himself rightly notes, has abandoned its twentieth-century alliance with social conservativism and adopted the agenda of the culture of death, becoming what has been derisively called on the internet “Woke Capital.”

The central objection to The Beer Option is the same often leveled at Dreher’s Benedict Option. There is little chance that a technocratic state will simply leave “Crunchy Catholics” alone at home with their Birkenstocks and homebrews.

As we work toward building Christendom 2.0, there is a need for heroes and martyrs in the public square as much as—or more than—stay-at-home organic gardeners and devotees of Fat Tire Ale.

Nonetheless, there is much wisdom in The Beer Option, a book that is best enjoyed along with a pint—or two.

Editor’s note: Pictured above is “Prosit!” painted by Eduard von Grützner.