Let us suppose there is such a thing as objective beauty. Suppose, along with the classical and Christian traditions, that the human person is made for beauty.

Now suppose further that beauty is a kind of composite, that the beautiful is made up of two parts, one metaphysical and the other psychological.

If such were the case, the well-being of all humanity would depend on keeping these two aspects of beauty together.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

I propose that beauty is indispensable to the fulfillment of all of us, and that beauty is made up of two parts, and that the horror of post-Christian civilization is that we are progressively cleaving these two aspects of beauty each from the other.

These two parts of beauty are “order” and “surprise.”

Order is the metaphysical part of beauty. It is historically expressed by such terms as “regularity,” “symmetry,” “perfection,” “integrity,” and “proportion.” It occurs when a thing is and acts in accord with its own nature.

Surprise is the psychological part of beauty, and is historically expressed by such terms as “newness,” “freshness,” “marvelousness,” and “brilliance.” Surprise happens when the attention of the human mind is arrested by something it does not find obvious.

Put these two parts together, and you have an aesthetic experience. You are startled by the goodness of reality, astonished by things working the way they’re supposed to, and delighted by the truth.

But order and surprise are a very difficult combination to achieve. After all, to the extent something is orderly, it grows predictable, and consequently becomes familiar and unsurprising. So you might naturally think that the only way to effect surprise is precisely to deviate from the natural order of things. Or you might think the only way to effect order, stability, and regularity is to take refuge in routine. You might think monotony is the price you pay for normalcy.

Not true. You don’t need to choose between order and surprise, and the reason is that we can always be surprised by forms, natures, essences, and the order that reveals them. Things are too rich for us ever to comprehend them fully—all things were conceived by the infinite mind of the Creator, and the depths of his brilliance in making things can’t ever be fully appreciated or exhausted by finite intelligence. So there’s always more with which reality can surprise us—there’s always more order, even in the things we know already.

Nonetheless, those who forget the intrinsic connection between order and surprise will think they need to pick one or the other. This disastrous alternative gives rise to the two substitutes for beauty, namely, surprise divorced from order (which is disorder) and order divorced from surprise (which we’ll call banality).

An easy escape from boredom into surprise, easier than working to perceive ever deeper levels of order, is to go against the nature of things.

A man who eats meat and vegetables isn’t doing anything surprising, whereas a man who eats books is. A woman who passes you on the street and smiles politely isn’t likely to surprise you; however, she will surprise you if she suddenly punches you in the neck, or walks suddenly into the street and gets hit by a car.

Now these examples may seem bizarre—and they are—but it’s a fact that fallen humanity has a strong attraction to the twisted, the perverse, and the disfigured.

Think of the many people who watch horror movies or the more horrendous phenomenon of snuff films. Think of the many people who used to pay money to see “circus freaks,” that is, who entertained themselves by looking at those suffering from particularly gruesome handicaps. Much of ancient literature, art, and culture was born of the pleasure of imagining people abused and warped in detailed ways (think, for instance, of Ovid’s Metamorphoses or of the public atrocities which entertained visitors to the Roman coliseum).

What’s going on here? How do people get to the point where they enjoy sickness?

I submit that we’re often tempted to pursue a good—namely, surprise—isolated from the order to which it ought to be joined. And when surprise becomes the only norm and the only goal, it instantly turns into perversion. When resources which are designed for beauty are used to simply shock, then we no longer celebrate or manifest reality—we attack it.

On the other hand, much of contemporary life pursues the other detached element of the beautiful, namely, order. Such is banality—order without surprise. This alternative claims to offer a guarantee of security and a warrantee of truth, goodness, and reality—but the whole thing is boring. It is stale and hackneyed and dull.

Think, for instance, of how the image of a white picket fence has become a symbol for family wholesomeness, respectability, responsibility, and financial stability. And how, at the same time, it sends shudders down so many spines. Having a white picket fence has become a cliché because it suggests a life that’s cliché and standardized, where nothing exciting, interesting, or worthwhile ever happens.

Or, to continue with the fencing motif, think of a chain-link fence which does nothing but function as a barrier. It’s cold, harsh, and ugly. True, it does what it’s supposed to do, but it embodies a concern for utility that has no interest in wonder or delight—that is, no interest in beauty.

This is the great danger of banality and of being cliché. Clichés hide the goodness and delightfulness of reality. It covers reality in a fog and makes it seem indistinct, grey, and homogenous.

When Does Banality Arise?

Whence arises banality? It is simply a result of laziness, and particularly from laziness of two kinds:

First, banality occurs through a careless use of established expressive forms. This is what is killing the white picket fence: it has been thoughtlessly overused. Every culture acquires an enormous treasure house of insights, incarnated in idioms, aphorisms, tropes, traditions, and artistic techniques and conventions. But those treasures need to be used thoughtfully or they lose their splendor.

If you’re doing your best to communicate a truth, it doesn’t matter if the formula is an old one—there is no cliché. But if you’re not doing your best to communicate something worthwhile, if you’re just grabbing the nearest platitude or stock image so you can have something safe to say, then it doesn’t matter how venerable or valid the form of expression is in its own right, you’ve made it a cliché. That’s an attack on beauty.

Remember, Our Lord doesn’t only say that we’ll be held accountable for every false or malicious word; he says we’ll be held accountable for every careless word (Matt. 12:36). Watch how you use expressive forms, and make sure they manifest, and not diminish, the splendor of reality.

Banality also happens through an overemphasis on efficiency. Roger Scruton describes this opponent of beauty as the “cult of utility.” It occurs when everything is governed by one simple principle, namely, achieving a material goal with as little expenditure of effort, time, and resources as possible. This is the chain-link fence: keep people in, keep people out, do it fast, do it cheap, do it reliably—and don’t worry about anything else.

Beauty demands that we celebrate order with creativity, surprise, and freshness. When efficiency is in charge, the only form order takes is monotony, mass production, and automation. The cult of utility dismisses beauty in favor of the useful. It covers the landscape with advertisements, solar panel fields, landfills, and plastic bags floating like tacky leaves in the wind. It manufactures cars that all look the same, builds big houses with identical structures, prepares enormous amounts of lousy food, prepackages it, and sells it cheaply and in bulk (supersized!). The cult of utility offers high-powered jobs with large incomes designed to maximize stockholder wealth, but not necessarily to make the world a better place.

Why do we go along with this craziness? Because it’s more profitable, more cost-effective, and quicker. In other words, it’s more convenient. It demands less of us. It would take much more time, effort, and self-sacrifice to produce things of beauty.

We need to choose between a consumerist lifestyle and a life of beauty. We can’t have both. Beauty will require sacrifice. But the alternative is banality and boredom, punctuated by guilty pleasures in the disordered.

Let me conclude with a formula for living beautifully taken from G.K. Chesterton’s magnificent little novel Manalive. There we are given the principle: break the conventions; keep the commandments.

Keeping the commandments ensures that we will have an ordered life, a life suited to our form and our natures and that our activity will be proportionate to our humanity.

Breaking the conventions means we won’t live according to the world’s standards and that we won’t get sucked into the paralyzing morass of vanity, cliché, competition, and empty social pressures which leads to uniformity without community.

That’s a good life. That’s a delightful life. That’s a beautiful life.

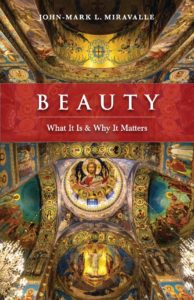

Editor’s note: you can order John-Mark Miravalle’s new book, Beauty: What It Is and Why It Matters, here.

(Photo credit: Church of the Gesu, Rome / Shutterstock)