I am part of a small circle of acquaintances of yesteryear—all 1968 alumni of the same college—who share stories, anecdotes, quotations, book recommendations, and video clips. Recently, we were treated to this declaration, attributed (without citation) to Thomas Jefferson: “I never considered a difference of opinion in politics, in religion, in philosophy, as cause for withdrawing from a friend.”

The quotation, ostensibly from Jefferson, elicited unexceptionable praise. After all, why would any one of us old acquaintances, buddies, and chums discard our fifty years of association due to a possible difference of opinion about such trivial matters as politics, religion, or philosophy?

I say “unexceptionable praise”—except for mine, which I withheld. Sometimes, all that one knows or believes can be challenged in and by a single sentence. As a teacher, deacon, soldier, and coach (not to mention husband and father), I have spent virtually my entire adult life arguing against the gist of Jefferson’s remark. Ironically, I learned this “anti-Jeffersonian” lesson at the very college the members of my quotation-sharing group attended.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

After all, who would be so arrogant, so intolerant, or so self-righteous that he would exalt religion or politics at the price of friendship?

Don’t flesh-and-blood relationships rank higher in the scale of things than cold, ideological principle? Isn’t loyalty to friends the highest virtue? Shouldn’t we agree with E.M. Forster (1879-1970) that “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country”?

II.

No, no, and no.

Throughout much of great literature, friendship is appropriately and wisely praised. One reads about friendship in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and in Sirach (especially in chapter six), among many other works of enduring significance. We conclude, prima facie, that Jefferson must have been right: given a choice between the call to be faithful to abstract principle and the competing need to be loyal to friends, we ought to choose the latter. That seems to be pretty much the contemporary consensus.

Friendship, though, is either meritorious or meretricious. If meretricious, the friendship is false, fraudulent, and fleeting. If meritorious, the friendship is true, trustworthy, and timeless. If meretricious, the friendship is built upon the sand of what is feckless, frivolous, or fun; if meritorious, the friendship is built upon the rock of what is paramount, permanent, and prayerful.

Here is the testimony of Psalm 101: “I will hate the ways of the crooked; they shall not be my friends. The false-hearted must keep far away; the wicked I disown” (Mundelein Psalter). This is the sense of Sirach 6: “Stay away from your enemies and be on guard against your friends.”

All loyalty, friendship, and camaraderie—as valuable as they are—only hold up to a point. They are circumstantial, conditional, and contextual; they are contingent upon conformity to what is good and true and beautiful, to what is consistent with both right reason and revelation (CCC #1954). When what purports to be a friendship is temptation to sin and evil, the friendship is already dissolved.

Suppose a friend were to ask you to help him do something manifestly criminal or sinful. Your response should be, first, to refuse and, second, to admonish the sinner, trying to convince him of the error of his ways and to win him back to doing what is right.

All this requires what is in short supply today: allegiance to transcendent standards. This idea was expressed clearly, concisely, and cogently by Pope St. John XXIII in Ad Petri Cathedram (1959):

All the evils which poison men and nations and trouble so many hearts have a single cause and a single source: ignorance of the truth—and at times even more than ignorance, a contempt for truth and a reckless rejection of it. Thus arise all manner of errors, which enter the recesses of men’s hearts and the bloodstream of human society as would a plague. These errors turn everything upside down: they menace individuals and society itself.

III.

The Jefferson quotation cited at the beginning of this piece, therefore, has it exactly backwards. It should read, “I consider a crucial difference of opinion in politics, in religion, [or] in philosophy a compelling cause for withdrawing from a friend.” What, then, does crucial mean?

In Robert Bolt’s superb play A Man for All Seasons, St. Thomas More is asked to betray truth and thus to ally himself with others (who have already betrayed that truth) “for fellowship.” More asks whether, when such a course of action leads to his being sent to Hell, his friends might then accompany him there “for fellowship.”

This is the crucial point. When a supposed friendship endorses evil or leads us down the path of sin (which used to be called formal or material cooperation with evil), we must have the prudence and fortitude to reject what is a false, fraudulent, and fleeting “friendship.” Those who would lead us to perdition are not our best friends but our worst enemies, and we must “withdraw” from them (having first counseled them as to the reason for the rejection).

The Marine Corps has an expression: “A Marine on guard duty has no friends.” We have no friends, either, if what we are guarding (2 Tim. 1:14) is assaulted by word or deed by those we thought to be friends, allies, colleagues, or comrades (including, by the way, those wearing collars).

“We must strain all our efforts,” as Aristotle told us, “to avoid wickedness, … [trying] to be good.” This way one may become another’s true friend. Without our own supreme and sustained effort at virtue (cf. 2 Pet. 1:3-11), there is no basis for friendship. Moreover, when we see that others are, or have become, corrupt, our responsibility is to flee from them, not to join in with them. Probably quoting the Greek poet Menander (c. 342-291 B.C.), St. Paul admonishes us: “Bad company corrupts good morals” (1 Cor. 15:33, 5:11, 6:9; Prov. 13:20, 2 Cor. 6:14).

There is, finally, a way to understand corrupt “friendship” and our obligation to withdraw from it, and even to escape from it. True friends and authentic friendship can all too easily dissolve in the moral acids of our day. These moral acids flow from the world (and its insistence that here and now is all there is), the flesh (and its insistence that physical pleasure is the principal point of all “relationships”), and the devil (against whose wiles we are today too rarely warned). These three enemies of the soul have wormed their way into our social mores and have found expression in music and other forms of popular culture.

IV.

False friendship is always grounded in one of these three evils: the (ironic) belief that there is no God, that virtue consists in supercilious self-exaltation, and that we can imagine a (Pelagian) world in which we are our own standard of right and wrong. (Note that Adam and Eve, in betraying God’s friendship, necessarily sullied their own relationship [see Gen. 3:5 and 6:5].)

True friendship is always grounded, knowingly or unknowingly, in pious devotion to God, in humble recognition of our sinfulness and our need for divine redemption, and with an educated understanding that there are, indeed, profound reasons for living and dying. Finding men and women who are morally and mentally committed to those truths is discovering “a treasure. Nothing else is as valuable; there is no way of putting a price on it” (Sirach 6:14-15).

If the late Father Richard John Neuhaus could ask if atheists can be good citizens, while replying in the negative (First Things, August 1991), I might similarly inquire if atheists can be good friends, while also replying in the negative. Authentic and appropriate loyalty to my friend is the fruit of my obedience to God (CCC #144, Rom. 1:5, 16:26), without which abject moral confusion is inevitable.

Is there a “way back” for soiled or sullied friendships? Yes. The way back is there for us, if we have the graced intelligence to see and to hear, and then to conform ourselves (Rom. 12:2) to God’s teaching. But moral discernment seems to have been sacrificed to today’s “divinity”: subjectivism, which tells us that we can do whatever we choose and imperiously walk away from the Bread of Life (John 6:35, 66).

Our Lord calls us his friends (John 15:15), but it is a friendship we may abandon—and too often do—at any time. When, by sin, we betray that first friendship, we lose the basis for all friendships.

If the first obligation of being a good friend is to be true to Truth, then the second flows from the first: having recognized the good, the true, and the beautiful ourselves, we must generously share that vision with others and resolutely call our friends who sinfully wander away back to it (James 5:19; Psalm 51:13).

Genuine friendship, like genuine community, may incorporate many people. It must always be based, however, not upon incoherent diversity of moral judgment (cf. 1 Cor. 5:1, 29-13) but rather upon devout unity of conviction as to what is wholly and infinitely lovable (Venite adoremus Dominum).

Jefferson, then, was wrong: true friendship demands that we withdraw from meretricious friends who befoul or betray what is pure, noble, and eternal.

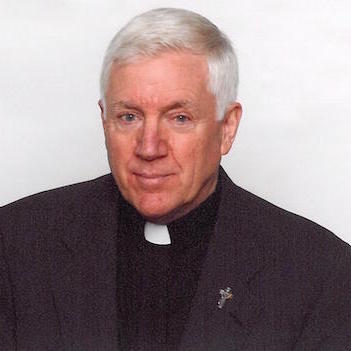

Editor’s note: Pictured above is a detail of “No Swimming” painted by Norman Rockwell in 1921.