There is no rest where you seek it. Seek what you seek but it is not where you seek it. ∼ St. Augustine

New York Post op-ed editor, Sohrab Ahmari, was twelve years old when he proclaimed himself an atheist. Angry about various things in his life, and alienated by the re-Islamization of his native Iran, he decided to curse God.

Nothing happened. So he pressed on.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

“How about this? There is no God!” he tauntingly added.

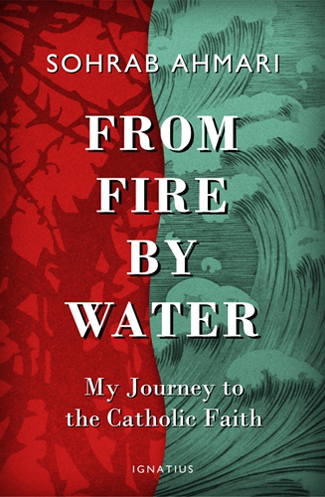

Little did Ahmari know how much he would ache at being in an Augustinian region of unlikeness, far away from God. Little did he know that he would one day write From Fire, By Water, an arresting modern-day permutation of St. Augustine’s Confessions.

Like Augustine’s spiritual autobiography, Ahmari’s compellingly written memoir is punctuated with soul-aches and poignant laments for misspent time. It brims with a final awe at the irruption of grace into a soul so wounded by sin. Ultimately this book is, as Cardinal Burke puts it, “not so much about Sohrab Ahmari but about the work of divine grace in his soul.”

Like Augustine’s spiritual autobiography, Ahmari’s compellingly written memoir is punctuated with soul-aches and poignant laments for misspent time. It brims with a final awe at the irruption of grace into a soul so wounded by sin. Ultimately this book is, as Cardinal Burke puts it, “not so much about Sohrab Ahmari but about the work of divine grace in his soul.”

Before his conversion to Catholicism, Ahmari says he dragged himself into a “netherworld of a kind.” First he became a high school nihilist and “goth” in small-town Utah, shocking his religious schoolmates with arguments in favor of abortion and post-birth infanticide. Then he became intoxicated with Nietzschean existentialism and the heady thought that God is dead.

“That infamous proclamation sent a frisson of transgression down my spine,” he recalls.

So Ahmari majored in philosophy and “did drugs and drank far too much” and “hooked up randomly if not frequently.” He ended up as a card-carrying Communist, thrilling in the license to “designate new values and overthrow the old.”

When he wasn’t flaunting his Marxist books in front of his Mormon roommates, Ahmari read the Beats, who “transfigured their debauchery into an authentic style.”

“Debauchery was the height of authenticity,” he thought.

One day, as a sort of gesture of contempt, Ahmari began reading St. Matthew’s Gospel in the King James Bible that his roommates had left on the couch. “Here we go with the hocus-pocus, blah-blah, Jesus is born, blah-blah, Jesus tells a parable, blah-blah,” he thought.

But when Ahmari got to the Passion narrative, he intuitively felt that Christ’s submission to death was “startling—and unspeakably beautiful.” The sacrifice left a “searing imprint” on his mind—even if he was still “hostile to its cosmic meaning.”

Ahmari clung to his pugnacious atheism for a while longer, meandering into postmodernism’s “demolition of all truth.” The one constant in his philosophical wanderings was his penchant for unquestioned relativism.

But relativism couldn’t soothe his conscience on those mornings when he woke up to the stench of post-drinking vomit.

“I prayed to God to condescend to my depths and wipe away my shame,” he recalls. His sense of conscience-haunted hedonism is reminiscent of Augustine’s own confession to God:

For you were always with me, mercifully punishing me, touching with a bitter taste all my illicit pleasures. Your intention was that I should seek delights unspoiled by disgust and that… I should discover it to be in nothing except you, Lord, nothing but you.

Later, as an undercover journalist traveling with Middle Easterners being smuggled into Europe, Ahmari discovered a haunting metaphor for his soul. He was in a house that “was a kind of charnel pit or Sheol, though the people in it were yet alive.” It was a void “on fire with degradation—and sin.” This was, Ahmari realized, an externalized reflection of his own hell-touched spiritual state.

Later, as an undercover journalist traveling with Middle Easterners being smuggled into Europe, Ahmari discovered a haunting metaphor for his soul. He was in a house that “was a kind of charnel pit or Sheol, though the people in it were yet alive.” It was a void “on fire with degradation—and sin.” This was, Ahmari realized, an externalized reflection of his own hell-touched spiritual state.

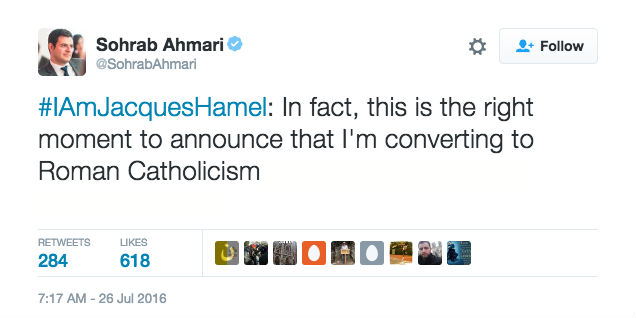

Eventually, after a series of increasingly irresistible divine knockings on his soul, Ahmari realized that both he and Augustine had “waded through the same river of error.” He saw his past for what it was: so much squandered time, lost in dissolute neglect of God and soul. He saw the philosophies of his youth as so many unsatisfying attempts to explain away the sin within him.

“Our Lord’s gift of radical absolution on the Cross was the only thing capable of repairing the brokenness in me and around me,” he concluded.

Ahmari’s last chapter brims with Augustinian spiritual thirst and exquisite descriptions of a Solemn High Latin Mass. This section’s epigraph could well be Augustine’s piercing cry: “Late have I loved thee, Beauty ever ancient, ever new, late have I loved thee.”

“Mass after Mass, I watched as others took Communion, and all I wished to do was to lie face down on the ground before the Sacrament in abject adoration,” Ahmari recalls. “There was no better proof of [Our Lord’s] presence than this desire.”

Kneeling before a statue of Our Lord, he repeated, some thirty or forty times: “Forgive me. Cleanse me.” Ahmari’s prayer was answered when he was baptized—with Augustine as his patron.

“There is no rest where you seek it. Seek what you seek but it is not where you seek it.” This Augustinian dictum, Ahmari says, could have served as his gravestone’s epitaph had he died before his conversion. Instead, by God’s grace, we have Ahmari’s moving testimony of his deliverance from fire, by water.