“Be sure that you wake me an hour before the dawn, and speak to me in these words: ‘My sister, if you are not asleep, I beg you, before the sun rises, to tell me one of your charming stories.’ Then I shall begin, and I hope by this means to deliver the people from the terror that reigns over them.”

The Arabian Nights: The Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night is, as the title might suggest, many things. It is a vast collection of stories having their origin in the ancient and medieval imaginations of the peoples who lived in the Middle East, Persia, India and South East Asia. It is also a window onto a world long lost to us. There is, of course, Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp, Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and all the charm and enchantment of their telling as well as that of many other, lesser-known tales. But there is also a wonderful strangeness, exotic and yet somehow familiar, a world in which we catch a faint reflection of our own.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

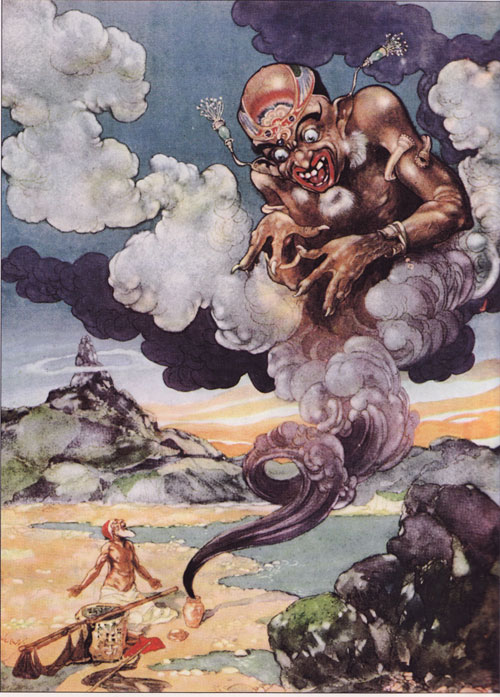

Framed by the story of Scheherazade and her courageous taming of the jealous fury of Shahriar, Sultan of Persia and husband to an unfaithful wife, The Arabian Nights encompasses bawdy tales (in the Burton translation, only) and tales of heroic virtue; false lovers and true; fables peopled with fierce genies and wicked magicians; hapless travelers harrowed by menacing monsters; fantastic landscapes and wild pranks. A veritable riot of genres!

Yet, for all its variety, the stories in the collection breathe the same air. There is, of course, the superficial similarity due to the eastern flavor of the narrative, dialogue, and characterization, especially pungent in Burton’s lush, arabesque translation. To take just one example, consider these opening lines from “The City of Many-Columned Iram and Abdullah Son of Abi Kilabah”:

It is related that Abdullah bin Abi Kilabah went forth in quest of a she-camel which had strayed from him; and, as he was wandering in the deserts of Al-Yaman and the district of Saba, behold, he came upon a great city girt by a vast castle around which were palaces and pavilions that rose high into middle air. He made for the place thinking to find there folk of whom he might ask concerning his she-camel; but, when he reached it, he found it desolate, without a living soul in it.

And there is, of course, the central story of Scheherazade, the occasion for the telling of all these tales. But I would like to suggest that there is a deeper cause of their unity, which is this: their deeply sympathetic understanding of the human condition. Taken together, the stories of The Arabian Nights constitute a balm for the wounded heart and a warning against holding the sins of one against all. A mirror held up to nature, reflecting an image of human weakness that is beautiful for its total dependence on God and its capacity to be redeemed, The Arabian Nights has the power to draw the self-righteous out of their terrible isolation. Jesting about scars is cruel in those who have never felt a wound, but often the salvation of those who have.

Evidence of this deep sympathy with the human condition comes in many forms. There is “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp,” in which a commoner wins the desire of his heart by  triumphing over a wicked magician and compelling the Sultan of a wealthy city in China to make good on his promise to give his daughter to him in marriage. One might expect the hero of such a tale to have merited his reward, but we are told in the first few lines of the story that Aladdin “was a good-for-nothing.” (The Arabian Nights, p. 213) Love for the Princess Buddir al-Buddoor and the lessons learned from his daring-do eventually transform the youth into a man who, with his wife, is capable of leaving behind “a numerous and illustrious posterity.”

triumphing over a wicked magician and compelling the Sultan of a wealthy city in China to make good on his promise to give his daughter to him in marriage. One might expect the hero of such a tale to have merited his reward, but we are told in the first few lines of the story that Aladdin “was a good-for-nothing.” (The Arabian Nights, p. 213) Love for the Princess Buddir al-Buddoor and the lessons learned from his daring-do eventually transform the youth into a man who, with his wife, is capable of leaving behind “a numerous and illustrious posterity.”

There is “The Story of Abou Hassan; or, the Sleeper Awakened,” which tells the dark comedy of the son of “a very rich merchant” in Baghdad who, through a strange series of improbable reverses of fortune, becomes Caliph for a Day, not once but twice, and through it all suffers terribly at the hands of Haroun al-Raschid, the cheerful but appallingly callous prankster Caliph. Yet Abou Hassan holds no grudges and in the end finds lasting happiness.

Then there is “The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor,” famous for its gargantuan monsters and harrowing adventures. Less well-known, perhaps, is Sinbad’s unstinting faith in God. (And one also apparently unknown to the editor of Stories from 1001 Arabian Nights, who chose to exclude all references to Sinbad’s faith.) A Job of the high seas, Sinbad refuses to curse God no matter how miserable the fortune allotted to him. At the end of all his voyages and safely back in Baghdad, the Caliph tells Sinbad that “he always hoped God would preserve [him]” (The Arabian Nights, p. 122), words that well express Sinbad’s deepest sentiments.

No one has suffered as we have suffered. Or so we think when we are under the lash of cruel misfortune. But there are worse things than suffering cruelty. As Plato argued in the Gorgias, it is better to be the victim of a tyrant than to be the tyrant himself. But, of course, it is better to be neither. And so we should not be surprised that the end of all these stories is the restoration of the Sultan’s mind to its right order. He credits his conversion to the chasteness, purity, ingenuousness and piety of Scheherazade. But we are also told that “when King Shahriyar heard her speech and profited by that which she said, he summoned up his reasoning powers and cleansed his heart and caused his understanding [to] revert and turned to Allah Almighty” (Burton, p. 522). There is a power in stories, and a power for good in all good stories. And that is perhaps the greatest wonder of this work of a thousand and one nights.

Works Referenced

The Arabian Nights, Illustrated Junior Library, illustrated by Earle Goodenow (New

York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1974);

The Arabian Nights: The Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night, translated by Sir Richard Burton, illustrated by William Harvey and the Brothers Dalziel (London: Collector’s Library Editions, 2007);

Stories from 1001 Arabian Nights: Aladdin, Sinbad, Ali Baba, and Others, translated by Andrew Lang (St.

Petersburg, FL: Red and Black Publishers, originally published in 1897).