“For I think that God has exhibited us apostles as last of all, like men sentenced to death; because we have become a spectacle to the world, to angels and to men. We are fools for Christ’s sake . . . . To the present hour we hunger and thirst, we are ill-clad and buffeted and homeless, and we labor, working with our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; when slandered, we try to conciliate; we have become and are now, as the refuse of the world, the offscouring of all things.” (1 Corinthians 4: 10-13).

On December 7, 1932, a young, female reporter spent the day spent the day covering the national “Hunger March” held in Washington, D.C. to protest the failure of government to address the worsening conditions of the Great Depression. A former communist and recent convert to Roman Catholicism, she had been struggling for several years as to how to integrate her concern for social justice with her new-found Catholic faith. Upon returning to her apartment following the march, she found waiting for her the man that would provide this longed-for integration. The woman was Dorothy Day. The man was Peter Maurin. In May of 1933, the two began publication of The Catholic Worker, a newspaper dedicated to promoting a Catholic vision of the reconstruction of society.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

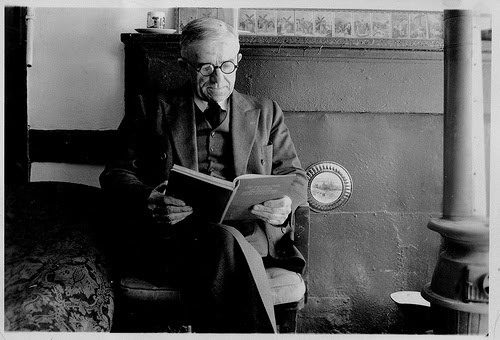

Dorothy Day went on to become one of the most famous American Catholics of the twentieth century. Though not without controversy, she has earned the admiration of Catholics across the political spectrum: Martin Sheen starred in Entertaining Angels, a film based on her life, while the late Cardinal John O’Connor promoted her cause for sainthood. Peter Maurin, the role Sheen played in the Day film, has received far less recognition. Day herself considered him the holiest man she ever knew, yet conceded he was something of an eccentric. Still, she remained convinced that he was a truly Christian eccentric, a holy fool in the tradition of St. Paul, or more specifically, St. Francis.

the political spectrum: Martin Sheen starred in Entertaining Angels, a film based on her life, while the late Cardinal John O’Connor promoted her cause for sainthood. Peter Maurin, the role Sheen played in the Day film, has received far less recognition. Day herself considered him the holiest man she ever knew, yet conceded he was something of an eccentric. Still, she remained convinced that he was a truly Christian eccentric, a holy fool in the tradition of St. Paul, or more specifically, St. Francis.

Maurin embraced and promoted holy poverty in a modern industrial age that presented new challenges to the Church’s understanding of wealth. Whereas St. Francis had stood against a greed and decadence acknowledged by the moral authorities of his age as a sin, Maurin set himself against a capitalist modernity that held up the pursuit of wealth as a positive virtue in itself. This new attitude toward material gain presented the additional challenge of fostering new inequalities of wealth even as it destroyed the traditional social bonds that had softened and humanized the old inequalities of traditional European Catholic societies. Secular critics of capitalism accepted the passing of traditional society as a positive good and focused on equalizing the distribution of wealth created by capitalist modernity. Maurin decried the poverty that he saw in the slums of the urban, industrial West, but saw both reformist and revolutionary plans for wealth redistribution as simply the democratization of greed. Against the modern alternatives of material poverty and material wealth, Maurin sought to lead the modern poor from their current, negative state of destitution—which combined material deprivation with social dislocation—to a future, positive condition of poverty, which allowed for the satisfaction of basic material needs but sought true wealth in communion with God and man.

Needless to say, this vision was a difficult sell in 1930s America. At a time when many American Catholics were still trying to achieve basic sustenance within the modern industrial system, Maurin was calling for a rejection of that system and a return to the traditional, rural communal life that had sustained the Faith in the pre-industrial age. Like Wendell Berry in our own time, Maurin was dismissed by many as a nostalgic dreamer. Also like Berry, Maurin knew the world of which he spoke. Born in the southern French village of Oultet in 1877, Maurin spent his childhood living as traditional a Catholic peasant existence as was possible in that place and time. Like many a rural youth faced with declining prospects within traditional rural society, Maurin eventually left his native village to attend school. Intended to improve his chances for success, education simply made Maurin more discontented with the modern developments he saw inexorably transforming the world around him.

Refusing to become a “boomer” and unable to remain a “sticker,” Maurin instead became a vagabond. He traveled the world working any number of industrial and agricultural jobs, all the while trying to imagine a humane and Catholic alternative to industrial capitalist modernity. A voracious and eclectic reader, he found his greatest inspiration in the social encyclicals of the popes, most especially Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum. Maurin was more skeptical than the popes on the possibility of Christianizing the industrial system through piecemeal reform, but he affirmed and developed their insistence that true harmony and the proper ordering of society would only come by drawing on the traditional philosophical and social principles that had sustained Catholic life in the pre-industrial age.

Maurin used The Catholic Worker to evangelize the working class in an authentic Catholic vision of society. Day and Maurin chose the title of their paper as a direct challenge to the communist Daily Worker. Much like Fulton Sheen, they believed that the collapse of the capitalist system left the modern West with a choice between Moscow and Rome. Still, Maurin articulated this Catholic alternative in an idiom likely to unsettle the average devotee of Sheen’s Catholic Hour. Maurin’s representative mode of expression was the playfully cryptic-yet-didactic prose poem he called the “easy essay.” Consider the following:

“Blowing the Dynamite of the Church”

Writing about the Catholic

Church,

a radical writer says:

“Rome will have to do more

than to play a waiting game;

she will have to use

some of the dynamite

inherent in her message.”

To blow the dynamite

of a message

is the only way

to make the message dynamic.

If the Catholic Church

is not today

the dominant social dynamic

force,

it is because Catholic scholars

have failed to blow the dynamite

of the Church.

Catholic scholars

have taken the dynamite

of the Church,

have wrapped it up

in nice phraseology,

placed it in an hermetic container

and sat on the lid.

It is about time to blow the lid

off

so the Catholic Church

may again become

the dominant social dynamic

force.

At a time when many were advocating a violent overthrow of the capitalist system, such rhetoric could appear incendiary. Maurin was, however, a committed pacifist. “Strikes don’t strike me,” as he was fond of telling Day. Maurin proved most controversial in his stand against even the most mainstream peaceful strategies for achieving social justice for workers. He rejected collective bargaining because he believed it conceded too much to the status quo and simply turned workers into capitalists, trying to carve out for themselves a bigger slice of what was at heart a poisoned pie. For Maurin, labor unions were as impersonal as corporations. The social crisis was a spiritual crisis, and the solution was the re-establishment of small communities capable of sustaining truly human, personal relationships.

Sadly, it was Maurin’s vision as much as his mode of expression that struck many, even some within the Catholic Worker movement, as foolish. In defense of Maurin’s vision, Dorothy Day wrote:

“Catholics are too apt to take the line that we must follow the lesser evil, as though there were no other choices. . . . Is there no choice but that between Communism and industrial capitalism? Is Christianity so old that it has become stale, and is Communism the brave new torch that is setting the world afire? Strange commentary that when Catholics begin to realize their brotherhood and betake themselves to the poor and to all races, then it is that they are accused of being Communists. . . . What chances are there for mass conversions these days when Statism has become a heresy that is engulfing even Catholics so that they do not realize that they are as materialistic as any Marxist?”

When Peter Maurin died on May 15, 1949, the New Deal order of welfare capitalism was ushering in an unprecedented period of prosperity that promised to satisfy every imaginable material desire. Catholics benefited materially from their support for this order, yet lost the family stability and communal solidarity that had marked them as a people apart in an earlier era. Twenty-five years later, when New Deal “statism” could no longer deliver the goods, many Catholics simply changed partners and danced to the tune of modern materialism’s other siren song, capitalism At present, we appear to be at the end of this second cycle of prosperity. As we ponder our next economic option, we might consider why it is that family and community structures that endured through centuries of material poverty have not been able to survive two generations of material prosperity. Which is more foolish: to think that social stability requires the subordination of material to spiritual ordering principles, or to affirm that social stability and spiritual renewal are compatible with the constant expansion of opportunities for material self-advancement? In reflecting on this question, few guides could be more reliable than Peter Maurin.

Sources:

Dorothy Day, with Francis J. Sicius, Peter Maurin: Apostle to the World (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004).