|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a five-part series by Dr. Smith in response to A Synoptic Look at the Failures and Successes of Post-Vatican II Liturgical Reforms by John Cavadini, Mary Healy, Thomas Weinandy and published in Church Life Journal. Future articles in this series will be published on successive Mondays.

A Rorate Caeli Mass embraces the attendees in an atmosphere of mystery, transcendence, and solemnity; it is very clear that something supernaturally wonderful is happening. I went to a Rorate Caeli Mass on a punishingly windy, cold, rainy morning—most fitting for an event marking emergence from darkness to light, from evil to goodness. The Mass began at 7 AM in a mostly dark church lit by hundreds of candles on the altar and in the church; everyone in the congregation was holding lit tapers.

The symbolism was impossible to miss. Advent is the time when we realize how dark the world is without Christ and how desperate we are for the light that He brings. The Mass is devoted to Mary who enabled that light to come into the world and enables all of us to be Christ-bearers.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

It was too dark for me to follow in my missal so “all” I did was meditate on those basic truths and luxuriate in the beautiful music and the dazzling candlelight. I felt completely engaged in the liturgy along with my fellow worshippers who also seemed enthralled by the occasion. (I wonder if our profoundly contemplative engagement qualifies as “active participation” or were we just passive woolgatherers?) I suspect the symbolism of the ceremony embedded itself deeply into the subconscious of the small children in attendance. It was certainly in my mind days after the event.

The Mass I attended was held in a parish Church that has recently been restored to its pre-Vatican II glory.1 Shortly after Vatican II it was “wreckovated” into what bore some resemblance to a bordello. Here are pictures of the Church through several of its stages.

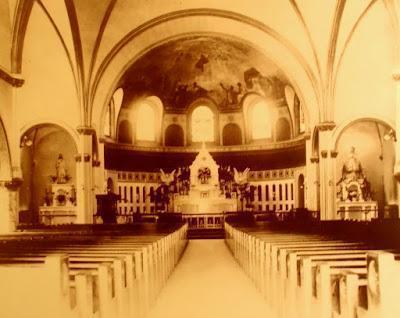

Original:

Slightly modified in 1939:

After Vatican II: “More renovations were made under the leadership of Msgr. G. Warren Peek, 1964–1993. Windows were covered and the apse was repainted gold. The high altar, reredos, marble angels, side altars and Communion rails were all removed. The sanctuary was extended, a simple, freestanding altar was added, and the first several rows of pews were rearranged”:

Restored in 2020:

The Rorate Caeli Mass was designed to be said in beautiful churches, with beautiful art and music; it would have been very much out of place in the bordello version of St. Thomas the Apostle, a design evidently considered fitting for the Novus Ordo—a Mass that has not spawned beautiful architecture, music, and art, but rather the opposite.

Sadly, most Catholics have never heard of a Rorate Caeli Mass, let alone attended one.

John Cavadini, Mary Healy, and Fr. Tom Weinandy (CHW) in their five-part series2 on the Traditional Latin Mass3 seem determined to make the Rorate Caeli Mass and all forms of the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) unavailable (though they do not state their exact intent).4 Certainly they said nothing about retiring the architecture, art, and music together with the liturgy that inspired it, and one cannot imagine that they would want to deny the faithful that beauty.

Nevertheless, the fact is that the TLM and such beautiful architecture, art, and music are based on the same theology—one CHW deem “inadequate”—and meant to be experienced together. CHW seem to have no sense of how devastating the loss of the TLM—and all its beautiful accouterments—would be to some very devout Catholics and how hard it will be, without it, to restore to the Church the beauty it had before the ravages of the modern age.

It’s a rare event when three well-respected theologians—noted for their fidelity—team up to write against a time-honored practice of the Church. CHW have put their impressive academic skills, considerable intellectual gifts, and well-deserved scholarly reputations in service of…discouraging and even perhaps abolishing the Traditional Latin Mass forever, a Mass that likely only 1–2% of Catholics currently attend.

I am sorry to say that the arguments that CHW offer are simply not up to the goal they have set themselves.5 For the last two or three years I have immersed myself in reading about the history and meaning of the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) and of the Novus Ordo (NO).6 The narrative that I discovered is remarkably different from that laid out by CHW, whose reading on the meaning and history of the liturgy and whose direct personal acquaintance with the current TLM and its attendees seem thin, to say the least.

Sadly, they do not worthily employ their skills of scholarship and reasoning in their critique of the TLM. The chief problems are that they omit evidence that works against their position; they draw conclusions not warranted by the evidence; they misrepresent the views of some theologians and some Church documents; they do not address the strongest arguments of the advocates for the TLM; they make arguments that are irrelevant to the question at hand; and they uncharitably depict the motivations of TLM advocates.

But before I respond to particular arguments put forward by CHW, let me explain why I find the project rather doomed from the start, if it is designed to convince any of us who now attend the TLM and have studied its history and that of the NO.

A Poor Deal

What we are to get in return for giving up the TLM is a “reformed” NO of some as-yet-unknown description. Reformed, because, as CHW readily and even frequently acknowledge, all too often the NO has proven to be a very inadequate form of worship. Indeed, never in the history of mankind have congregations been subjected to such faith-destroying, banal, silly, and even blasphemous versions of the liturgy. Those are not everyday occurrences to be sure, and yes, there are “reverent NOs” (I have attended many and still do), but few adult Catholics have not encountered or heard about a NO that has shocked and offended their Catholic sensibilities, and in some parishes and some parts of the world this is the rule rather than the exception.

CHW say we are to overlook these abuses as glitches in the performance of the NO since it is still “young” and trust that the abuses will eventually be a thing of the past and that it is possible that some future form of the NO will have all the virtues of the TLM—without its flaws—and more. Of course, I pray that happens, but I am not foolish enough to be willing to give up a liturgy organically one with the most beautiful architecture, art, and music the world has ever known for a liturgy that is perfectly at home in some of the ugliest churches ever built, with sing-song tunes offered as hymns, and abstract art without aesthetic or religious value. Case closed for some of us.

In short, the kind of art, architecture, hymns, and poetry that the TLM has inspired compared with that of the NO is pretty much in itself a sufficient “argument” that we cannot and must not let the TLM be taken from us again.

But when respected Catholic scholars spend their valuable time trying to convince others that the Mass used by the Church for at least a millennium and a half is a danger to the faith, a response is in order. Indeed, some will be persuaded simply because it is CHW who are critiquing the TLM, and their witness will be trusted. I believe my analysis of their position will show that trust to be misplaced.

There are many who are much more capable than I of responding to the arguments of CHW—some have already done so7—but I want to add my voice to the cry of those who find antipathy to the TLM among faithful Catholics, and learned ones at that, to be perplexing in the extreme.

After all, those who attend the TLM to a person have a profound devotion to the Eucharist; they study the Mass inside and out; they withdraw their children from pernicious public and Catholic schools; indeed, they make great sacrifices to drive a long way with their many children who are evidently quite content to attend a liturgy long and peculiar—though fascinating—to them. These families and other attendees at the TLM produce a greatly disproportionate number of vocations to the priesthood and life-affirming marriage. But none of that seems to matter to CHW.

It would require a book to respond to the series in detail; what I have written is a partial response that gives representative samples of what seem to me to be patently unfair and weak scholarly and argumentative approaches to the question.

Age of the TLM

Factual errors in the articles undermine confidence in how much CHW know about the TLM. For instance, they claim that the TLM is just “400 years old” and that the Tridentine Mass was a “reform” of the liturgy. All sound scholarship indicates, however, that the TLM goes back to the early stages of the Western Church and was found in its essential Latin form 1500 years ago (if not longer), not 400 years ago. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger made this point emphatically:

There is no such thing as a Tridentine liturgy, and until 1965 the phrase would have meant nothing to anyone. The Council of Trent did not “make” a liturgy. Strictly speaking, there is no such thing, either, as the Missal of Pius V. The Missal which appeared in 1570 by order of Pius V differed only in tiny details from the first printed edition of the Roman Missal of about a hundred years earlier. Basically the reform of Pius V was only concerned with eliminating certain late medieval accretions and the various mistakes and misprints which had crept in. Thus, again, it prescribed the Missal of the City of Rome, which had remained largely free of these blemishes, for the whole Church. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, The Feast of Faith: Approaches to a Theology of the Liturgy (Ignatius Press:1986) 85

The Mass of the sixth century resembled the TLM much more than the NO resembles the TLM—just as the other ancient liturgies of the Church, such as the Byzantine liturgy, resemble the TLM more than they do the NO in regard to a host of characteristics.8

Again, Pope Pius V in 1570 did not introduce a “new” or “reformed” liturgy but codified a form of the liturgy that was already in place, his missal being nearly identical to the one published a century earlier in 1474, and this, in turn, very like the missal of Innocent III from the early thirteenth century. Changes made were largely in accord with the wishes of those in remoter areas of the Church who wanted to have their liturgies be in conformity with prestigious and ancient Rome.

There is absolutely no similarity between the 1570 codification of what was already in place well before then and the introduction of a “new rite” in 1969. Moreover, Pius V permitted the continued saying of any rite or use of Mass that had been said for at least 200 years, whereas Pope Paul VI wanted the TLM completely suppressed (although he made a few exceptions for elderly priests and for Agatha Christie and friends in England!).9

Latin as Vernacular

Another factual misconception the CHW perpetuate is the oft-refuted claim about the reason that the traditional liturgy of the Church was conducted in Latin; they say:

Earlier, the Mass came to be celebrated in Latin in the western Church not because it was a sacred language but because it was the vernacular of its day; likewise, earlier still, with Greek. Jesus himself employed Aramaic, the vernacular of his time and place. If he had not, the apostles would have had no clue as to what he was doing at the Last Supper, nor could they then have actively participated in that first Eucharistic liturgy. The same holds true for the faithful today.

But Latin was not “the vernacular” in all places when it was chosen. It was the official, bureaucratic language of the Roman empire, an empire that included many peoples whose native language was not Latin; it was not the “vernacular” for them. Moreover, scholarship has shown that the Latin of the liturgy was a highly refined or “cultic” version of language, not the language “of the people”; it was, in fact, chosen because it already had features of a sacral or hieratic language and was utilized in part for that reason.10

The reference to the Last Supper is a red herring, for two reasons: first, Jesus would have celebrated much of the Passover in the (by then sacral) language of Hebrew, which was not the common language of his day and place; and second, we still have a “clue” what is going on at the liturgy even when we don’t understand the language. I have been to Melkite liturgies and others where I understand nothing of what is being sung, but I know precisely the kind of event in which I am participating—and participating actively because I am conscious of what the event is and the response it demands of me in faith, adoration, and love.

The Liturgical Movement and Bouyer

CHW attempt to tie the NO to the Liturgical Movement that preceded it, as though the NO were the logical and perhaps inevitable development of that movement and were embraced by Vatican II (VII). What CHW fail to mention is how unwelcome some of the proposals of the Liturgical Movement were to the authorities in the Church. Indeed, the primary aspects of the Liturgical Movement that made their way into the Sacrosanctum Concilium, the constitution on which the Fathers of Vatican II voted, were the call for some use of the vernacular in the Mass and a call for more active participation on the part of the laity.

CHW quite selectively report on the Liturgical Movement and particularly on some of the views of the individuals cited. For example, the work of Fr. Louis Bouyer is cited, who wrote on the history of liturgical movements and reported that at different periods in Church history, reform of the liturgy was needed, but the reform generally involved removing inappropriate accretions.11

While CHW acknowledge that Bouyer “was not entirely happy, during and especially after the Council, for he anticipated and after observed the subsequent liturgical aberrations, both theological and pastoral,” that demurral is a serious misrepresentation of his sharply expressed disgust with how the NO was composed and with the NO itself. There are few individuals who have written more acerbically about Vatican II and the NO, both ventures in which he was closely involved. He is famous for this claim:

You’ll have some idea of the deplorable conditions in which this hasty reform was expedited when I recount how the second Eucharistic prayer was cobbled together. Between the indiscriminately archeologizing fanatics who wanted to banish the Sanctus and the intercessions from the Eucharistic prayer by taking Hippolytus’s Eucharist as is, and those others who couldn’t have cared less about his alleged Apostolic Tradition and wanted a slapdash Mass, Dom Botte and I were commissioned to patch up its text with a view to inserting these elements, which are certainly quite ancient—by the next morning! …. I cannot read that improbable composition without recalling the Trastevere café terrace where we had to put the finishing touches to our assignment in order to show up with it at the Bronze Gate by the time our masters had set.

I prefer to say nothing, or little, about the new calendar, the handiwork of a trio of maniacs who suppressed, with no good reason, Septuagesima and the Octave of Pentecost and who scattered three quarters of the Saints higgledy-piggledy, all based on notions of their own devising! Because these three hotheads obstinately refused to change anything in their work and because the pope wanted to finish up quickly to avoid letting the chaos get out of hand, their project, however insane, was accepted. Louis Bouyer, The Memoirs of Louis Bouyer: From Youth and Conversion to Vatican II, the Liturgical Reform, and After (Angelico Press, 2015), 221–23.

A theologian who writes such words in his memoirs can hardly be included in a list of enthusiasts for the NO or Vatican II! The sort of criticisms we have quoted from Bouyer can easily be found in other theologians and bishops who were closely involved in the liturgical reform. Expression of regrets about what happened and even of support for the return of the former rites are by no means rare in the literature, but no one would know that from CHW’s series.

Articles in this Series:

Part I: Sacrificing Beauty and Other Errors (February 6, 2023)

Part II: Misrepresentation of Mediator Dei, Sacrosanctum Concilium, and Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI (February 13, 2023)

Part III: The Genesis of the Novus Ordo and “Theological and Spiritual Flaws” of the TLM (February 20, 2023)

Part IV: Unity, Charismatic Masses, and Africa (February 27, 2023)

Part V: Mischaracterization of the TLM, Then and Now (March 6, 2023)

- These pictures and the description of the “bordello” version were taken from http://detroitchurchblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/st-thomas-apostle-ann-arbor.html. The picture of the renovated Church is available online here.

- All five articles have been merged into one: John Cavadini, Mary Healy, Thomas Weinandy, “A Synoptic Look at the Failures and Success of Post-Vatican II Liturgical Reforms” (Church Life Journal, Dec. 1, 2022); accessed Dec. 6, 2022 (hereafter, “A Synoptic Look”).

- I prefer the term “Traditional Latin Mass” to “Tridentine Mass” since “Tridentine Mass” can be interpreted (as often is) to suggest that a new Mass was invented at Trent when in truth Trent codified the Order of Mass that had remained essentially the same with organic developments since about the fourth century.

- It seems to be a reasonable interpretation of their articles to conclude that CHW think that the Church would be better off without the general availability of the TLM and indeed, would be better off if it were more or less confined to the dustbins of history. They do not explicitly say they think that the TLM should be abrogated but do say: “we believe that a return to the Tridentine Mass is liturgically unfortunate and doctrinally unacceptable,” and “To return to the Tridentine Mass is, then, to lose or obscure a foundational dimension of the Church and her worship.” They also ask about traditionalists: “Do they [traditionalists] really expect that hundreds of years from now the Tridentine Mass will still be celebrated, even unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ at the end of history?” The answer to that question is that the advocates of the TLM do think it will be celebrated hundreds of years from now, a prospect unthinkable to CHW. Although their piece so contemptuous of the attendees of the TLM is likely to persuade them of deficiencies in the TLM, they ask attendees of the TLM “for the well-being of the Body of Christ, to return to the Church’s ordinary liturgical form.” They certainly never address the possibility of any accommodations to the Traditional Latin Mass community.

I sent a query to the authors for a clarification about what precisely they are proposing as to the availability of the TLM—does saying there should be no “return” to the TLM mean that it should not replace the NO or that it should not be available at all? I heard back only from Mary Healy, who acknowledged that my questions were good ones but that she does not have the time to give them the attention they deserve.

Certainly, it can be said with confidence that CHW intend to discredit the TLM and to discourage people from attending it. It is not unreasonable to think they would like to see it abrogated, so I will be using “discourage/abolish” when speaking of their intention; if they intend otherwise, I welcome a clarification from them.

It may also be worth noting that I submitted these essays to the Church Life Journal in hopes that they would be interested in hosting a thorough and fair response to CHW. I received only an automated response and withdrew the article after they had it in their possession for several weeks.

- I must thank Dr. Peter Kwasniewski for his help on my response; he provided invaluable bibliographical and editorial help, often sharpened my argument, and encouraged supplementation of my analysis in important ways. The critique remains mine but has been much improved because of his input.

- This is the list of books I have purchased; I have read many in their entirety; the others in part. (I am not showing off; it is just that there is such a wealth of material, I couldn’t resist building at least a basic library of resources, most on the TLM but also on criticisms of Vatican II. There are also, of course, countless informative articles on the internet.) Romano Amerio, Iota Unum: A Study of Changes in the Catholic Church in the Twentieth Century (Kansas City: Sarto House, 1996); Louis Bouyer, Liturgical Piety (Providence, RI: Cluny Media, 2021); idem, The Memoirs of Louis Bouyer: From Youth and Conversion to Vatican II, the Liturgical Reform, and After (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2015); Yves Chiron, Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2018); Michael Davies, Liturgical Time Bombs In Vatican II: Destruction of the Faith through Changes in Catholic Worship (Rockford, IL: TAN Books, 2003); Roberto de Mattei, The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story (Fitzwilliam, NH: Loreto Publications, 2012); Michael Fiedrowicz, The Traditional Mass: History, Form, and Theology of the Classical Roman Rite (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2020); Klaus Gamber, The Reform of the Roman Liturgy: Its Problems and Background (San Juan Capistrano, CA: Una Voce Press and Harrison, NY: The Foundation for Catholic Reform, 1993); Thomas G. Guarino, The Disputed Teachings of Vatican II: Continuity and Reversal in Catholic Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018); Prosper Guéranger, The Traditional Latin Mass Explained (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2017); Matthew Hazell, Index Lectionum: A Comparative Table of Readings for the Ordinary and Extraordinary Forms of the Roman Rite (N.p.: Lectionary Study Aids, 2016); Bryan Houghton, Judith’s Marriage (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2020); idem, Mitre and Crook (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2019); idem, Unwanted Priest: The Autobiography of a Latin Mass Exile (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2022); James Jackson, Nothing Superfluous: An Explanation of the Symbolism of the Rite of St. Gregory the Great (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2021); Peter Kwasniewski, Reclaiming Our Roman Catholic Birthright: The Genius and Timeliness of the Traditional Latin Mass (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2020); idem, Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2014); idem, Tradition and Sanity: Conversations & Dialogues of a Postconciliar Exile (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2018); idem, The Holy Bread of Eternal Life: Restoring Eucharistic Reverence in an Age of Impiety (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2020); idem, Noble Beauty, Transcendent Holiness: Why the Modern Age Needs the Mass of Ages (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2017); idem, The Once and Future Roman Rite: Returning to the Traditional Latin Liturgy after Seventy Years of Exile (Gastonia, NC: TAN Books, 2022); Matthew L. Lamb, ed., The Reception of Vatican II (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); idem, ed., Vatican II: Renewal within Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Ulrich L. Lehner, On the Road to Vatican II: German Catholic Enlightenment and Reform of the Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016); Elizabeth Lev, How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2018); George J. Moorman, The Latin Mass Explained: Everything Needed to Understand and Appreciate the Traditional Latin Mass (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 2010); Aidan Nichols, Conciliar Octet: A Concise Commentary on the Eight Key Texts of the Second Vatican Council (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2019); John W. O’Malley, What Happened at Vatican II (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010); Aurelio Porfiri, Uprooted: Dialogues on the Liquid Church (Hong Kong: Chora Books, 2019); Lauren Pristas, The Collects of the Roman Missals: A Comparative Study of the Sundays in Proper Seasons Before and After the Second Vatican Council (London/New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2013); Joseph Ratzinger, Theological Highlights of Vatican II (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2009); Athanasius Schneider, The Catholic Mass: Steps to Restore the Centrality of God in the Liturgy (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2022); idem, The Springtime That Never Came: In Conversation with Pawel Lisicki (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2022); H.J.A. Sire, Phoenix from the Ashes: The Making, Unmaking, and Restoration of Catholic Tradition (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2015); Bernard Tissier De Mallerais, Marcel Lefebvre (Kansas City, MO: Angelus Press, 2004); George Weigel, To Sanctify the World: The Vital Legacy of Vatican II (New York: Basic Books, 2022); Brian Williams, Why Tradition? Why Now? (Clackamas, OR: Regina Magazine, 2018); Ralph Wiltgen, The Rhine Flows into the Tiber: A History of Vatican II (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 2014).

- Among others, see Peter Kwasniewski, “A More Realistic Appraisal of the Liturgical Movement and Its Destructive Descent.” One Peter Five, September 21, 2022; Joseph Shaw, “A Reply to Cavadini, Healy & Weinandy,” Rorate Caeli, November 25, 2022; Sam Keyes, “The Failures of Reform: A Response to Cavadini, Healy, and Weinandy,” Covenant, December 13, 2022; Dom Alcuin Reid, “The One Thread By Which the Council Hangs: A Response to Cavadini, Healy, and Weinandy,” One Peter Five, January 19, 2023.

- See Peter Kwasniewski, “The Byzantine Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and the Novus Ordo—Two Brothers and a Stranger,” New Liturgical Movement, June 4, 2018

- K.V. Turley, “The Mystery of the ‘Agatha Christie Indult,’” National Catholic Register, November 5, 2021.

- For an explanation of Latin as a sacred language, see Christine Mohrmann, Liturgical Latin: Its Origins and Character (Catholic University of America Press, 1957); Peter Kwasniewski, “Why Latin Is the Right Language for Roman Catholic Worship,” Rorate Caeli, June 4, 2022.

- Louis Bouyer, Liturgical Piety (Providence, RI: Cluny Media, 2021).