Editor’s note: The following essay by Deacon Toner is a response to Prof. John Paul Meenan’s critique of Deacon Jim Russell’s defense of President Truman’s decision to use atomic weapons against Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

President Warren Harding, not a bright man, is supposed to have said, as he mulled over certain economic questions, that he listened to one group of advisors, who told him X, and that seemed right. Then he listened to another group of advisors, at odds with the first group, who told him Y, and that seemed right. Of the presidency, Harding then said, “[Expletive deleted], what a job this is!” Let us season criticism of any president with a dash of pity.

I.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

Someone misrepresents his credentials or purposes, gains access to Planned Parenthood, and is subsequently able to expose to the world images of the barbaric practices there. That misrepresentation is a lie; we must never lie; therefore, the actions of that person, however good his intentions might have been, must be condemned.

We know that the end cannot justify the means and that we may not do evil that good might come from it. Start down that slope, and soon we begin to see ourselves as gods, capable of any action—or no action—provided we profit by our decision. To lie is to sin, and we must not sin.

The Doctrine of Double Effect provides, we think, a remedy when we are confronted with dueling duties such as our obligation to expose the butchery of Planned Parenthood but also have the responsibility never to lie to acquire incriminating data about them. The elements of the DDE, however, do not, in my judgment, solve the great problems, principally because we may choose to do evil, while telling ourselves that what we are doing is only oblique or peripheral to our main action, whereas, in fact, the “oblique action” is central. (See P. A. Woodward, ed., The Doctrine of Double Effect.)

We know better than to cite a “greater good” argument, for “greater good” implies “lesser evil,” and we must not do what is wrong even though it results in what is right. It is, we learn, never right to do wrong.

I have taught military ethics for decades, and I have heard it said, many times, that the bombing of Hiroshima was “good.” It was not good: it was a horror of enormous proportion. What the United States did on August 6, 1945 was horrible.

Because all sin is, in fact, horrible, was lying to the employees of Planned Parenthood also wrong? No, it wasn’t; and the case is helpful to us, I think, as we think about Hiroshima.

Had I been able to, I would have participated in the deception at Planned Parenthood in a heartbeat because not to have participated (had I been able) would have been much “wronger.” There is an “innate moral sense,” Peter Kreeft has argued (and been skewered for, by the way) that leads us to know that Pro-Life “deception” was acceptable in the Planned Parenthood case.

I know the ethics. I know the arguments. I know the debate. But what the action at Planned Parenthood achieved is eminently morally defensible on the grounds, I believe, of the natural moral law, which is written on our hearts.

We devise codes of ethics and, indeed, schools of ethics (deontology, teleology, etc.) to guide and govern us in ordinary circumstances. As Cicero (106-43 BC) told us, however, we must never seek to replace the quiet counsel of the natural law with rules, tenets, or principles which may supersede or impede our call to do what is right and to refrain from what is wrong (cf. CCC 1956, 1 Thess 5:21-22). Can it be that a rigorist, pharisaical attachment to an ordinary rule may subvert doing what is good in extraordinary circumstances? Can it be that occasionally eisegetic reading of and attachment to a given biblical pericope can cloud judgment and undermine belief or action which is more truly consistent with what we ought to do (cf. Rom 12:2), especially during a moral emergency?

II.

Much as I respect my fellow Catholics who criticize those who lied to Planned Parenthood, I must dissent from their views and applaud those who supererogatorily lied to keep babies alive. Does anyone think that a merciful God will, in his good time, judge severely those who lied to get information which allowed them, in turn, to tell the truth about the barbaric practices at Planned Parenthood? Are there times that a good universal law (don’t lie) may equitably yield to particular exemption (to save babies)? Are there times that a good universal law (don’t bomb cities) may equitably yield to particular exemption (to end the Pacific war)?

Is it mere jingoism to write that Truman was right in 1945, or is it, rather, a kind of moral intuition that leads us to say that he did the right thing at the right time in the right way for the right reason? This does not mean that we don’t deeply regret its necessity or that we don’t deplore the circumstances leading up to it. We surely do. But we also recognize that an atrocious military power in the Pacific—the Japanese imperial empire—had to be promptly defeated, and that we had the means of expeditiously effecting that defeat. For Truman not to have used those means would have been an egregious dereliction of public duty. Consider the geopolitical circumstances.

It is, let us say, 1949. Truman had two atomic bombs to use to persuade intransigent militarists in the Japanese government to end the war. Suppose he chose in 1945 not to use them. The war has now dragged on for four pitiless years (and it might have gone on much longer than that). Civilians and soldiers continued to die in large numbers in Japanese occupied lands. Many thousands of Americans, Japanese, and others have perished in the invasion of Japan (Operation Olympus) and in the subsequent brutal guerrilla war through Japan, and on other islands. Countless more American prisoners of war have now died in the barbaric prisoner of war camps run by the Japanese. Thousands more young Americans have been pressed into military service, and there is no post-war boom—no G.I. bill, no new housing, and no baby-boomers. Europeans are starving by the thousands because there is no money for a Marshall Plan. Almost all of Europe is now behind the Iron Curtain, for there is no money (and there are no men for soldiers in Europe) to prevent that aggression. Now (1949) the Soviet Union, too, has atomic weaponry. Then the press breaks the news: Truman, who had been elected in his own right to the presidency in 1948 had had the atomic bomb in 1945 after FDR died, but chose not to use it! Millions of Americans are outraged by that decision of their commander-in-chief. The country sinks into chaos as the House of Representatives impeaches Truman, certain to be convicted by the Senate on grounds of treason (Constitution, Article III, Section 3, Clause 1).

Thus, what appears good (not using the bombs) would have produced gravely disproportionate evil (continuation of the war and its disastrous corollaries). To refuse to use the bombs would have been wrong masquerading as right, evil disguised as good. Be careful, then, of pure absolutes, the practical application of which requires discernment and prudence. Truman had no other reasonable or moral choice than to follow the course he did.

III.

In using the bombs, Truman and his political and military advisers made a decision which we, in 2017, are free to condemn. We do not know, though, the sins of omission—what would have happened had Truman not used the bomb? Excellent books such as Richard B. Frank’s Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire or Fr. Bill Miscamble’s The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs and the Defeat of Japan are rarely cited, or read, by those who condemn the bombings. Instead, there are those (but certainly not Professor Meenan) who brand Truman as a sadistic murderer, or as a racist intent upon slaughtering the Japanese, or as a political psycho trying to impress the Russians (read Gar Alperovitz), or maybe eager to justify the financial cost of the Manhattan Project.

The bitter criticisms come glibly. They could have used a bomb against a desert island (but the effects, we know, would not have been persuasive). They could have used diplomacy against the Japanese militarists (but reading the histories of the day certainly convinces us otherwise). They did not wait for a last resort (there never is a “last resort”). They violated the stipulations of jus in bello (an example of petitio principii or begging the question). How effortlessly flow the animadversions years after the event.

In the literature of Christian ethics, there is something called a “graded absolute” or a “qualified absolute” (see Norman Geisler, Christian Ethics), but I’ll refrain from a recitation here. The graded absolute, though, helps us understand the unique moral circumstances surrounding the end of World War II, which was an emergency of extraordinary dimension, calling, in turn, for extraordinary measures. The use of those “measures” depended upon the values, virtues, and views of political and military leaders whose schooling in ethics was based, chiefly, upon the development of their character and their integrity. I believe they made a terrible and a terrifying choice, but one that, in fact, was just, for it brought about the end of a war which, in the absence of bombings, would have dragged on, probably, for many years, resulting in manifest grave evil. Truman and his advisers had no template, no urim and thummim, no military or moral manual, to consult to determine if the Enola Gay could and should fly on August 6, 1945. They did their duty as they were given light to see that duty.

Is this mere covert utilitarianism? Do we count the bodies, real and probable, and then bless the bomb(s)? Emphatically, No. As there was no precedent for Hiroshima, neither has there been (thank God) precedent based upon it—the subsequent use of atomic/nuclear weapons. The atomic powers learned a savage lesson from the horrors of the bombing. The atomic bombings were, in my judgment, unique and unparalleled. Attempts to fit them into a paradigm are Procrustean. We try to propose a series of ethical formulas to “approve” or to condemn these bombings; that is how ethics instruction usually works. But I suggest that there is no neat paradigm here. Given the nature of the war in the summer of 1945, Truman, I think, did what he had to do.

“Duty,” the now-besmirched Robert E. Lee once said, “is the sublimest word in the English language.” We have, for some time now, been eager, metaphorically, to tear down statues of Truman, Marshall, Byrnes, Stimson, and others. Fulfilling their duty, they acted as public servants ought to act—to save the lives of countless human beings. Is that not a coded way of saying that the end justifies the means, a crass consequentialism? Dean Acheson, Truman’s Secretary of State, answered the question this way: “If you object that that is no different from saying that the end justifies the means, I must answer that in foreign affairs only the end can justify the means; that is not to say that end justifies any means, or that some ends can justify anything.”

The point: the critical nature of what we call aretaic or virtue ethics—it matters, tremendously, whom we elect to office and whom we commission to lead our soldiers, airmen, sailors, and Marines. In judging Truman, keep prominently in mind the fact that he acted manfully and wisely in unique circumstances—a good human being, trying to be a good public servant.

As Lincoln once said, “It is my earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter. And if I can learn what it is, I will do it! These are not, however, the days of miracles, and I suppose it will be granted that I am not to expect a direct revelation. I must study the plain facts of the case, ascertain what is possible and learn what appears to be wise and right.”

We live, as our faith tells us, in a vale of tears. I do not say that reconciling our political nature and our moral destiny is ever easy. We must do the very best we can, as I think Truman and his advisors did.

Truman and the others have, by now, had to answer for their actions. I believe, and pray, that they received merciful judgment, for I believe, and pray, that they did what was called for under very difficult circumstances and in very perilous times.

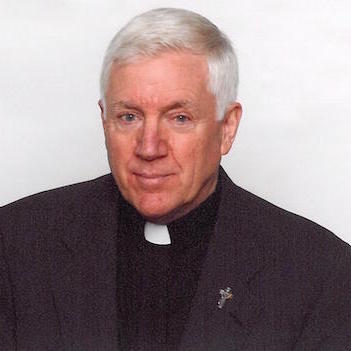

Editor’s note: Pictured above is the Japanese surrender aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. In the foreground, General Yoshijiro Umezu is signing the surrender terms for the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters.