Charity. Forgiveness. Love. Mercy. Peace. Here is the heart of the Gospel, the core of the classic Christian message. Should we, then, find someone today who models these ineffable virtues and seek to elect him, or her, to the presidency? Should a person of such transcendent noble character serve as a diplomat, a military leader, a police officer? What does it say of us if we hesitate in approving such a proposal?

The law of love is the chief teaching of Our Lord and of his holy Church (Mark 12:30-31). There is, however, a complementary warning or admonition which we see throughout the Bible—and throughout history. It, too, is a central and traditional Christian teaching, telling us about concupiscence, the human tendency toward evil. Representative pericopes would include Jeremiah’s lamentation about our moral sickness (17:9), Our Lord’s description of the evil in our hearts (Mk 7:21-23, John 2:25), and St. Paul’s repeated caution to us about attraction to evil (Romans 7:14-20, Galatians 5:17, and Ephesians 2:3, among many others).

To teach or preach about love, mercy, and peace is comparatively pleasant. To teach or preach about sin and evil is, by contrast, more demanding, more exacting, and—I speak from experience here—a much less popular subject. Similarly, to be told or to read about the joy of Heaven is calming; to be told or to read about the fires of Hell is much more disturbing.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

After a homily about sin which I gave in a state different from the one where I am now, the priest counseled me that he wanted the homily to uplift and inspire the parishioners, not to upset and disturb them. I managed to restrain myself by not asking if he might be excessively worried about being popular (as in John 12:43 or 1 Thess. 2:4) or suggesting, tongue in cheek, that the homily not be given immediately before the collection.

The point, though, remains: all of us have a need of hearing and reading that we are called both to the ideal of love and to the reality of Christian prudence (see The Catechism of the Catholic Church, #1806). We are called to love all other human beings, and even ourselves.

When we send our kids out on Halloween, however, we parents either accompany them or issue stern warnings about where they can trick-or-treat and how any received candies are to be inspected before they are consumed. There are many nice people who give kids candy. There are also monsters out there who put poison or razor blades in such candy.

Love without prudence is perilous; prudence without love is paranoid.

The Catechism teaches that “Sin is present in human history; any attempt to ignore it or to give this dark reality other names would be futile” (#386). We are tempted, the Catechism continues, “to explain [evil] as merely a developmental flaw, a psychological weakness, a mistake, or the necessary consequence of an inadequate social structure” (#387 cf. #412).

The implications of the fact of sin, though, are enormous. Any good parent must learn to say, “No,” even though the children want permission or approval of something which parental prudence rightly rules out. Similarly, there are many times in which Holy Mother Church must say “No.” Even though we children want what we want when we want it, the Church, in her wisdom, may rightly rule it out.

“Conscience cannot come to us from the rulings of society,” wrote Bishop Fulton J. Sheen; “otherwise it would never reprove us when society approves us, nor console us when society condemns.” The Church wrestles with the principalities and the powers, “against the world rulers of this present darkness” (Eph. 6:12). “Ignorance of the fact that man has a wounded nature inclined to evil gives rise to serious errors in the areas of education, politics, social action, and morals” (CCC #407).

In other words, there are monsters out there.

There are monsters out there who would sell the body parts of slaughtered babies.

There are monsters out there who would promise heaven from massive governmental programs only to deliver the hell of a totalitarian nanny state.

There are monsters out there who, on a pretext, would seize an American college student and treat him in such a way that he would lapse into a coma and die shortly after returning home.

There are monsters out there claiming that real education denies, excludes, and ridicules what is sacred only to deliver, like Frankenstein, a profane indoctrination which cannot tell right from wrong, good from evil, or virtue from vice.

There are monsters out there who will kill, corrupt, deceive—and lie, cheat, and steal—to build a modern Tower of Babel in which all things decent are defamed and in which all things noble are denounced.

And, horrible to say, there are monsters out there who would molest children and then hear confessions and preach sermons.

And the job of the Church is to say, with St. Paul: STOP! “Some people there [at Ephesus] are teaching false doctrines, and you must order them to stop” (1 Tim. 1:3).

We live at a time of hyper-optimism, such that Micawber or Pollyanna or Pangloss would enjoy. All we must do for prosperity, we hear, is to believe political parties or personalities that tell us they can provide all we need, and that they will permit anything we want (cf. CCC # 2526), if we give them our souls. But the Church tells us that this is a vale of tears, that we must conform ourselves to the true teaching of Christ the King, and that we will all face divine judgment.

In the Church, we must again hear Father Thomas Merton (1915–1968), wise in this admonition if, regrettably, not so always: “You must know when, how, and to whom to say, ‘no.’ This involves considerable difficulty at times. You must not hurt people, or want to hurt them, yet you must not placate them at the price of infidelity to higher and essential values.”

And in politics, we must again hear James Madison (1751–1836), the “Father of the Constitution,” who prudently asked: “What is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself” (Federalist #51).

“Citizens,” as Gaudium et Spes at one point told us, “… either individually or in association, should take care not to vest too much power in the hands of public authority nor to make untimely and exaggerated demands for favors and subsidies” (#75). Don’t feed the monsters.

In days of giddy optimism, a prudent Church and a prudent statesman must warn us against expecting too much from any human agency. Wrote the French Catholic Charles Peguy, killed in World War I, “It will never be known what acts of cowardice have been committed for fear of not looking sufficiently progressive.” The heroic Admiral James B. Stockdale (1923–2005), who spent over seven years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam, once told me that he did not want optimistic fellow prisoners.

Properly pessimistic prudence teaches us that there are monsters out there whom we must stop by wise Church teaching, by government which administers lightly and ceases its endless erection “of New Offices, and [sending] hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance” (Jefferson, in the Declaration of Independence), and by masculine military policies which recognize that, in this fallen world, there are real enemies—and real monsters, whom we must, at appropriate times and places, resist, repel, and rout.

This requires wise priests, judicious teachers, seasoned diplomats, and good soldiers—all of whom have the learning to know when to say “No” to evil practices, the temperance to control themselves, and the courage to confront and to stop the monsters out there.

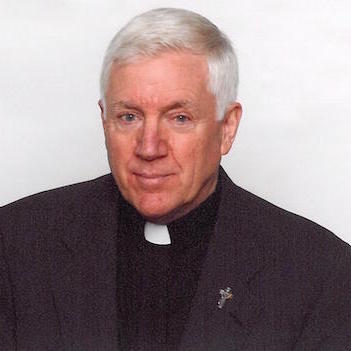

Editor’s note: Pictured above is “Dante and Virgil Encountering Lucifer in Hell” painted by Henry John Stock in 1922.